This story was originally published March 11, 2016.

You've probably seen this memorial if you've ever driven on Lamar Boulevard in Austin. It's right there, on the pillar holding up the train bridge where Third Street crosses Lamar.

It says: "Fair Sailing Tall Boy. Ivan Garth Johnson. Not forgotten. 1971 - 1989. Don't Drink and Drive, You Might Kill Someone's Kid."

Lynett Oliver doesn’t know Ivan Garth Johnson. She doesn’t know anything about him. But if you’re like her, you can’t help but wonder: What’s the story behind this memorial?

“The thing I find really powerful about it: It’s this person, whoever did this – Mom, Dad, sister – that’s immortalizing this kid’s life, and it’s a life that had really just begun,” Oliver says.

She asked us to investigate the story behind the memorial for our ATXplained project.

There’s not a lot to go on from the memorial itself. No one signed it. And 1989, when Ivan apparently died, was a long time ago – especially in Austin. But with some Googling, I tracked down Ivan’s story.

Before the crash

Bruce David Johnson wipes the dust off a photo of Ivan that sits on his bookshelf. Bruce David is Ivan’s dad. His beard, now white, hangs over the front of his overalls.

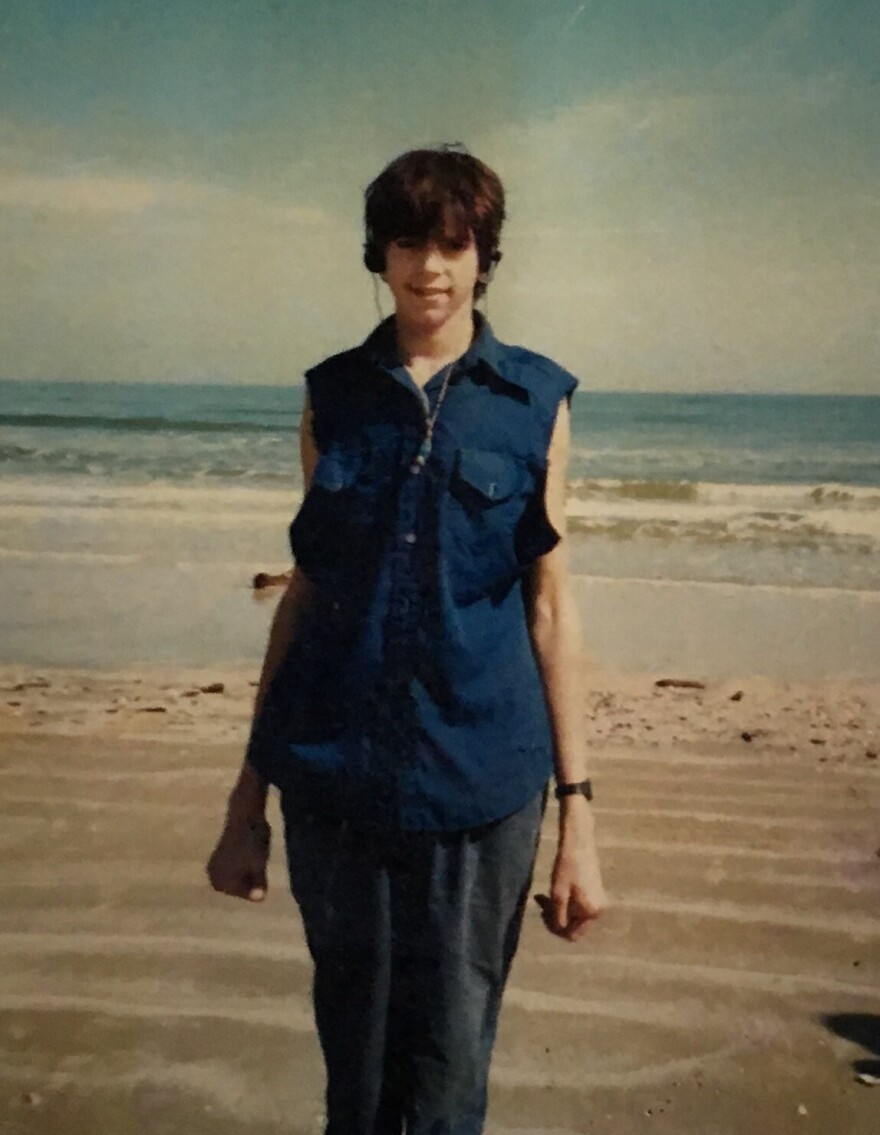

Ivan was a handsome kid. Tall and thin, sporting an unmistakable '80s haircut in the photo.

Bruce David keeps file cabinets full of journals chronicling his entire life – and Ivan's, starting from his birth on Nov. 8, 1971.

“I was 18 years old, so that was pretty young. I don’t recommend it," Mary Boyd, Ivan's mother, says with a chuckle. "Still, I don’t regret it either.”

Mary and Bruce David didn’t stay together for long after Ivan was born.

Ivan was born with something called Marfan Syndrome.

“It makes him long and skinny – little body fat,” Mary says. And it gave him long fingers, too. “It’s called arachnodactyly, which means spider fingers. And, so he was kind of Spiderman, and he could climb over all kinds of stuff, and he was a very clever child. Everybody loved him.”

Ivan was homeschooled for a while before going back to public school at Austin High School. But Mary says he didn’t seem to look too far into the future.

“It seemed like he really didn’t have any idea what he was going to do, you know, as an adult," she recalls. A friend of hers told her she had seen Ivan in the weeks before he died. "She was talking with him, he was starting to get a little mustache, because he was 17. And she says, ‘you’re getting a little mustache.’ And he goes like, ‘What? Huh? What?’ like ‘No, I’m not growing up. I’m not, no.’ And she said, she thought maybe the reason that he didn’t have any clue what he was going to do is some part of him knew he wasn’t going to grow up. He wasn’t going to be an adult.”

The crash

It was Monday, July 17, 1989. Ivan was 17 years old. His truck had broken down. Bruce David had towed the truck back to his house in South Austin to fix it. Then, he and Ivan headed back to North Austin to drop Ivan off at Mary's.

They were headed up Lamar, just over the bridge across Town Lake. Meantime, another driver, who had been at Barton Springs drinking beer with a friend, was speeding up Lamar, too.

According to the police report, the drunk driver was weaving around slower cars, going over the speed limit, and hit Bruce David's car in the back right side. The impact pushed Bruce David's car up onto the median and smashed the passenger side into the support column on the railroad bridge.

“Ivan was in the passenger seat," Bruce David says. "He was belted in, but the side collision – the belt didn’t help him.”

“[Ivan's] head hit that column. He was killed instantly,” says Mary.

Mary, of course, didn’t know any of this yet. Bruce David was badly injured and in a coma that would last several days.

'The Pacific Ocean of pain'

That night, Mary was getting worried when she hadn’t heard from Ivan. She called Bruce David’s house, and someone there told her there had been an accident and she should call the hospital. So she called the Emergency Room.

Eventually, she was put on the phone with Bruce David’s wife, Ivan’s stepmom.

“I said ‘Dottie, how is Ivan?’ And she said, ‘He didn’t make it Mary.’ And I said, ‘He’s dead?’ She said, ‘I’m sorry’ and I just screamed ‘No.’ Like it just ripped out of me at the top of my lungs.”

Mary says the pain was beyond anything she could fathom.

"It’s orders of magnitude beyond what you ever imagined," Mary says. "I mean, it’s the Pacific Ocean of pain. That’s what I felt like at the time.”

Mary says a kind of insanity set in after Ivan’s death. It changed her. She couldn’t worry about all the little stuff most of us agonize over. The grief, she says, was written on her face. Many of her friends abandoned her.

There were good things, though. That year, she would meet the man who she would later marry.

The memorial

It was November 1989, right around what would have been Ivan’s 18th birthday, that Mary started to think about a memorial.

"I was thinking about what should I do, and this friend suggested a heart with ivy leaves…because 'Ivy' was one of his nicknames,” she says. She knew right where to put it: under the train bridge, the place where Ivan died.

Beyond it being the place where he died, Mary also want to cover up a piece of graffiti that was on the pillar.

"It was the number four in a circle with a slash through it, which I interpreted to say ‘for nothing.’ And I couldn’t have that," she says. "One of the big things people who have children that die worry is that their children will be forgotten, or that their death was for nothing. So I had to change that. That couldn’t stand.”

So she made some stencils, recruited a friend to help distract the police (if needed) and headed out to the bridge.

“I put up the first stencil and did all the red, and I was like crying and I’m like, ‘Is this red enough?’ and [her friend] goes ‘Yeah, that’s very red,’" recalls Mary.

That's when the cops showed up. Her friend tried to tell them what was happening, but finally, an officer came over to Mary and said, "‘You have to stop that now.’ I’m like ‘okay.’ I pulled it off. It’s done.”

Mary and her friend actually ended up getting arrested, but the memorial was finished.

So what do the words mean?

"‘Fair sailing’ is from an old Austin jug band song about Amelia Earhart," Mary explains. "Ivan wanted to fly. He wanted to fly ultralights. He never did."

And he was tall – 6' 3" – so that's the "tall boy" part.

What about "Don't drink and drive you might kill someone's kid"?

“Oh, [it came] from my heart, you know," says Mary. "It’s like, wake up. This is for real. You could kill someone’s kid. And a part of it was also about that his life can’t be meaningless, and I don’t want him to be forgotten. And this is the meaning of his death. He was killed by a drunk driver. People need to learn from that. That’s important.”

Every year, Bruce David makes a heart out of cedar with the number of years since Ivan’s death – and sets it at the base of the pillar.

'It belongs to Austin'

The memorial has been defaced a few times over the years. Mary fixed it once back in the 1990s.

“I actually even added another word, ‘Not forgotten’ in there, which I hadn’t in the first one," she says. "I think I improved it.”

Then a couple years ago, somebody painted over the bottom part of the memorial. Mary intended to fix it, but then she found out someone else had already done so.

Stephanie Scott says she'd driven past the memorial every morning for more than a decade, so when she saw it had been defaced, “I was just so angry. To cover up someone’s emotional pain like that, and that it’d been such a part of Austin," Stephanie says. "You know, that it’d been there since 1989.”

Stephanie recruited her friend Amberly Worley to restore the memorial.

“I just got some acrylic paint and came with Stephanie, and she watched me to make sure I wouldn’t get put in jail," Amberly explains. "I just had the reference photos from before it was vandalized, and I tried to make it look exactly, or as close to exact as I could.”

“I’m glad that we could kind of take on that burden for [Mary]," Stephanie says.

"It’s not just Ivan now," says Amberly. "It’s so many other people that have lost kids, and it’s a reminder for all of those other people in addition to Ivan. I feel like lots of people are looking at it not as just one person, but as all their children that have been killed by drunk driving.”

For her part, Mary Boyd is happy that others – people she doesn't even know – are looking out for Ivan’s memory, too.

“I’m so grateful to her because it kind of makes me feel like it belongs to Austin now. It’s not just mine. It’s not just Ivan’s memorial. It belongs to Austin.”

Ivan Garth Johnson would have turned 52 years old in November 2023.

_