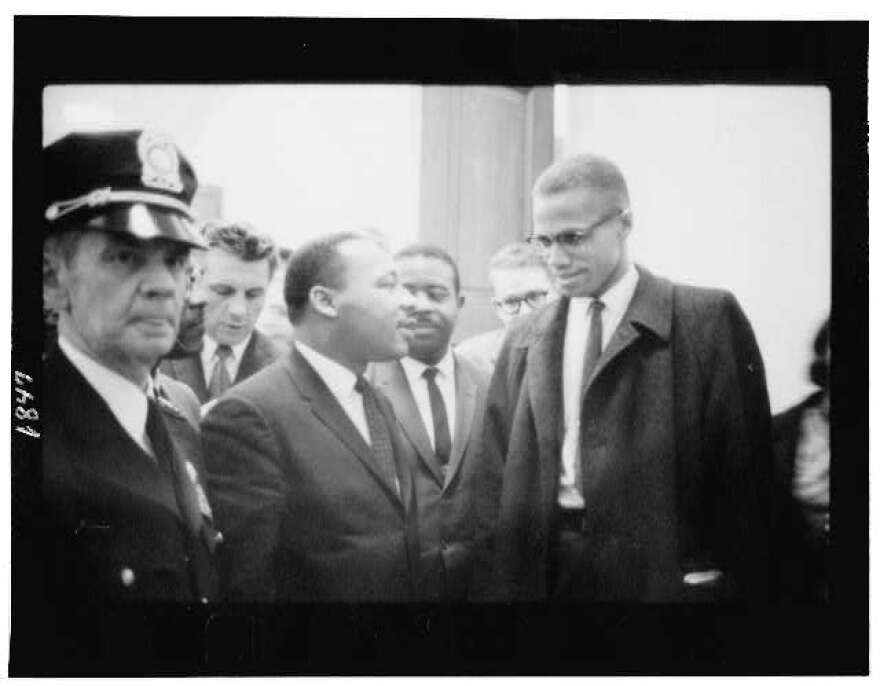

Peniel Joseph writes that Martin Luther King Jr. is "most comfortably portrayed as the nonviolent insider," while Malcolm X "is characterized as a by-any-means-necessary political renegade."

But those familiar biographies, he says, don't capture the nuanced evolutions their activism and politics underwent during their lives.

Joseph is the Barbara Jordan Chair in Ethics and Political Values at the LBJ School of Public Affairs and is the founding director of the school's Center for the Study of Race and Democracy. He acknowledges that for decades, students of history had "to pick a side" in understanding the philosophy and tactics in the fight for civil rights in the United States in the 1950s and 1960s. (By the way, Joseph says he was on "team Malcolm" as a younger student.)

In his book The Sword and The Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr., Joseph extracts Malcolm X and King from that "either/or" narrative:

A full appreciation of Malcolm and Martin and the historical epoch that shaped them requires taking them down from the lofty heights of sainthood and rescuing both of these men from the suffocating mythology that surrounds them.

Listen to the interview below or read the transcript to hear more from Joseph about how King and Malcolm X "have different tactics and strategies," but "over time, those tactics and strategies actually converge" and continue to impact movements for justice today.

This transcript has been edited lightly for clarity:

Peniel Joseph: Malcolm X is not just this political sword; he’s also a person who's talking about human rights. He actually says that if whites were willing to peacefully integrate racially, even before he left the Nation of Islam, he'd be fine with racial integration. He just felt that Black people shouldn't have to beg to be accepted in this society and be treated as citizens.

And King is not just this peaceful warrior. He's absolutely this nonviolent civil rights leader. But he comes to bring the sword, too. And that sword is this movement against not just racial injustice, but poverty and war. King breaks with Lyndon Johnson over the Vietnam War. King organizes this poor people's campaign, which is this multiracial, multicultural struggle. King is really a big critic of American democracy and the gaps between the rhetoric of American democracy and its reality.

KUT: Why did each of them evolve in the way that they did over time?

Joseph: Malcolm really feels that structural racism and the histories of racial slavery and white supremacy in the United States really mandate that it's going to take force to bring about Black dignity in the United States. And what he means by dignity is an end to poverty, an end to police brutality, an end to forced racial segregation.

He says there's a difference between racial separation and racial segregation. I think over time, Malcolm starts to see — not just after leaving the Nation of Islam but while in the nation of Islam — that things like voting rights matter. Trying to transform democratic institutions actually matter. Political coalitions matter. The only way to produce that Black dignity that he's been preaching as part of the Nation of Islam requires reaching out and being more adaptable and growing his worldview. He travels to the Middle East in 1959 and then again throughout 1964 and Europe. And that's going to transform his worldview as well.

Political experience inspires change for Martin Luther King, Jr. After the March on Washington and after the passage of the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act, one of the key moments for Dr. King is the Watts uprising in Los Angeles. So that happens August 11, 1965, five days after Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act. And he sees so much poverty and so much brutality in Los Angeles, King starts to see that to achieve his notion of radical Black citizenship is not just one free of racial oppression, it's one that includes rights. And the rights are rights to food justice; rights to a decent housing; rights to guaranteed living wage, good jobs, a decent life. He starts to see that he needs to go further and have a bigger critique.

As the 1960s progress, he starts to make an argument that the only way American democratic institutions can be transformed is from the bottom up. Not forcefully, never forcefully. But is it revolutionary? Yes, he's interested in redistributive justice and that's where they start to converge.

KUT: Is there kind of a line, though? Violence, nonviolence. Is there sort of a non-negotiable there because they didn't overlap there?

Joseph: They didn't overlap there. And those are issues of tactics. I think that they both, by 1964, believe that political coercion is going to be required. Malcolm never takes violence off the table, but he does say that if the United States has a real commitment to human rights and that white liberals have a real commitment to human rights, they can be part of this movement to transform society.

King — violence is never on the table, but King acknowledges that the growing gap between the rich and poor means the country's more susceptible to violence. King always describes riots as the language of the unheard and the oppressed.

KUT: Reexamining and reclassifying or expanding the narratives of Malcolm X and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. — does that then necessitate looking at the 1950s and the 1960s of our history a little differently?

Joseph: Absolutely. I think it really makes us reexamine and reimagine these movements for racial and economic and political justice in the 1950s and the 1960s and their relationship with the political liberalism of the 1960s and the 1950s.

And it really connects us to today because we think about Malcolm and Martin and things like March for our Lives; and women's marches; obviously, the Black Lives Matter movement; marches for immigration rights; and for the rights of Muslims; and the rights for trans people and LGBTQ; this intersectional justice. Those two were really some of the coauthors of those movements. The movements that we have today have further expanded what they were talking about.

But they were really thinking about identity and citizenship and freedom in extraordinary ways. And I think by pigeonholing them as that sword versus that shield, we really lose the nuances and the subtleties of that period.

KUT: I'm wondering also if those old narratives stick in place because they were written mostly by white people.

Joseph: The journalists of the period were predominantly white who set us up with the framings of Malcolm and Martin. Absolutely. There is a Black press that has a different framing of both of them. But the Black press' framing has not won out when we think about textbooks and we think about our common knowledge collectively.

I do think that right now we have much more robust African-American history that's being written by a range of people. But certainly, Black scholars have a chance to shape the interpretation of the way in which these figures are being thought about and the legacies that they have in our contemporary time in a way that they didn't in the 1950s and the 1960s.

Both Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. are revolutionaries. They're going to have different tactics and strategies. But over time, those tactics and strategies actually converge both in their lifetimes — and what's so interesting about both of their assassinations is that they leave terrible holes and voids. But those issues are still struggled with throughout the next decade up until today.

The movement didn't end. But what you did lose were these principal figures who were able to attract both outsized media attention globally and also able to attract political coalitions based on people who were interested in the way in which they articulated the quest for both citizenship and dignity.

Got a tip? Email Jennifer Stayton at jstayton@kut.org. Follow her on Twitter @jenstayton.

If you found the reporting above valuable, please consider making a donation to support it. Your gift pays for everything you find on KUT.org. Thanks for donating today.