It had been seven hours, 51 amendments and years of work. Lawmakers on the floor of the Texas Senate were tired, and state Sen. David Sibley was talking about a can of beans on St. Patrick’s Day 1999.

“Starting in 2002, people will be able to shop. If they don’t like the electric provider they’ve got, they can switch,” he said. “If the price of a can of beans goes up 10 cents, people shop somewhere else. If the price of electricity goes up, people for the first time will have a choice on what they’re going to do. It’s no more business as usual.”

Two decades ago, the Waco Republican led the charge to deregulate Texas’ electrical market — a move that would make the state’s system unlike any other in the United States.

It had been a slog. You could hear it in his firm but plaintive tenor ahead of the final approval of Senate Bill 7, the measure that deregulated the state's retail electrical market. It was, and is, unlike any other system in the country — one that, years later, would leave millions of Texans without power after a catastrophic freeze.

Deregulation was pitched as a way to lower Texans' electricity bills by spurring competition in a market that was dominated by regional monopolies. But it also built in new threats to the system by allowing energy providers and traders to shift the blame and avoid accountability whenever the power supply became unreliable.

SB 7 was a bill that had been years in the making but began in earnest in 1998 on a cocktail napkin.

A Plan Takes Form

Sibley was on a flight back to Texas with Democratic Dallas state Rep. Steve Wolens, his Texas House counterpart who was shepherding legislation to deregulate the electric market; and Pat Wood, the head of the Public Utility Commission of Texas, the statewide agency that regulates utilities like electricity, water and telecommunications.

They had gone to California on a reconnaissance mission. After federal regulation paved the way for deregulated electrical markets in the 1990s, many states started crafting plans to do so. Texas and California, the two most populous and energy-rich states in the country, were both pushing to be the first state to successfully deregulate their markets.

California beat Texas to deregulating retail electricity, passing a bill in 1996. So Sibley, Wolens and Wood flew to California to scope out their market, jotting down their takeaways and concerns on a napkin on the flight back.

After Texas state lawmakers deregulated electricity for wholesale customers in 1995, many pushed for doing so on a retail scale, as it would, ideally, provide relief to Texas ratepayers every month on their electric bills.

Texas lawmakers tried in 1997, but failed. The bill ultimately took a backseat to then-Gov. George W. Bush’s plan to overhaul public school finance.

But Sibley was tapped to break up the electric utilities' regional monopolies, push competition into the market and get the least expensive electricity onto the grid.

Texas had unique advantages. For one, California relied heavily on energy imports. About a fifth of the state's energy comes from hydroelectricity that's imported from the Pacific Northwest. Texas was, and still is, the leading energy producer in the U.S.

On top of that, Sibley and his allies said they saw an opportunity to create a more efficient system and sell cheaper electricity than California.

California had set up a complicated system of selling and regulating energy trades on both the retail and wholesale market — and an equally complicated system to regulate trades. Sibley would have to find a more workable, less onerous, system for Texas.

California also set up a system to cap its electrical rates if the market got too volatile. Sibley argued that could financially cripple investor-owned utilities like the Golden State's largest energy utility, Pacific Gas & Electric, under the right market conditions.

Similar utilities in Texas would be the largest opponents to deregulation, as they’d likely be broken up under the new system.

Alison Silverstein, a staffer for the Public Utility Commission of Texas in the 1990s who worked with Wood, said the political weight and sway of legacy utilities was undeniable.

“Utilities have always been large players, or at least until tech became so dominant in the economy,” she said. “Utilities used to be hugely politically influential in governor’s offices and legislative offices.”

Sibley knew this firsthand. He accepted thousands in political contributions from utilities in 1997.

Knowing they were headed for a confrontation with those utilities, Sibley, Wolens and Wood set about to shore up as much support ahead of Jan. 12, 1999, when lawmakers would gather again in Austin for the legislative session.

The Players

Ahead of the session, a tenuous alliance formed between industry groups, environmentalists and energy firms.

Industrial customers who used massive amounts of electricity (like factories, manufacturing plants and oil refineries) had been a loud voice in calling for deregulation in 1999, just as they had in 1995, when Texas deregulated its wholesale electrical market. Deregulation, for them, meant less overhead costs.

For environmental groups, the scheme was an opportunity to bust up the old, coal-fired utilities — while also getting in on the ground floor of a new system that could get more, cleaner power on the Texas grid.

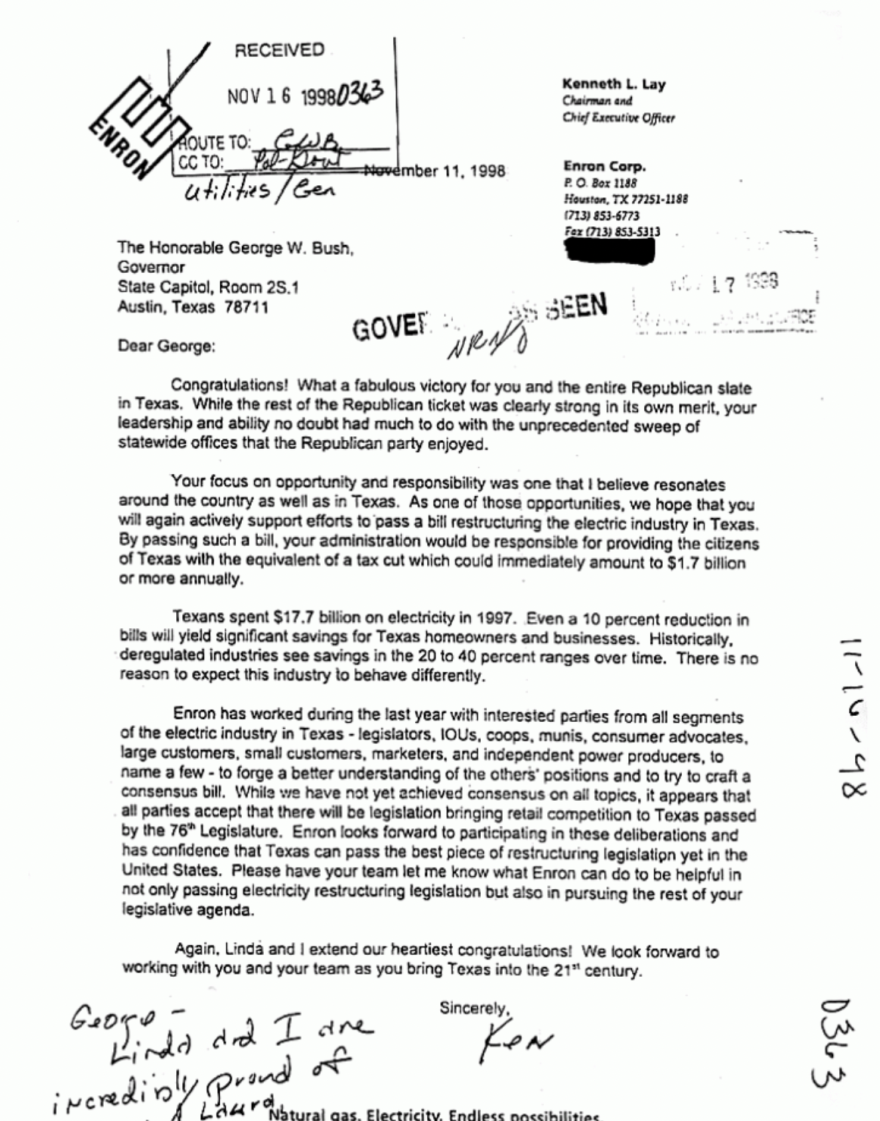

Then there was Enron, whose founder Ken Lay was friends with Bush, donated thousands of dollars to his two campaigns for governor, and personally wrote him letters calling for Texas to deregulate its market — one in 1996 and another in 1998.

Aside from utility monopolies, the biggest obstacle in the way of Sibley’s way was, perhaps, Texas’ electrical cooperatives and its municipally-owned utilities.

Deregulation, for them, was an existential threat, as lawmakers could require those utilities to split their transmission, generation and marketing, as they planned to with investor-owned utilities.

Here’s The Deal

To gain the support of municipally-owned utilities and cooperatives, Sibley promised them exemptions from the bill.

Environmental groups were assured the new market would be one that spurred innovation — and clean energy like solar.

Energy traders were pretty much guaranteed a profit under the new system — one in which they would commoditize energy and sell it like a stock or bond on a financial market. That system would make them billions, and still does.

Prior to the legislative session in 1999, Sibley, Wolens and Wood had shored up consensus among the major players. Sibley recalls getting them to commit to a bill sight unseen.

“At that point, they didn't care really what else it did as long as they weren't in it. So, they pledged and nobody knew,” he said. I mean, we did this I remember it like during the Christmas holidays. Nobody was in the Capitol. So, they came to my office individually. I told them what the deal was.”

SB 7 was drafted in the basement of the Texas Senate, Sibley said. he didn’t even trust the Texas Legislative Council — the state’s legal counsel for lawmakers — to look over the drafts.

“I didn't trust them. I felt like if we used the Texas Legislative Council, it would be leaked to the various lobbyists,” he said. “And people would have a chance to start sniping at it before we ever even released.”

In his State of the State on the opening day of the session, Bush said he “look[ed] forward to working with Senator Sibley and Representative Wolens on an electric deregulation proposal that will cut costs for consumers while making sure electricity is available and reliable.”

Little did he know — or anyone, really — that Sibley had already drafted the plan.

Nine days later, the Waco Republican unveiled the bill on the Senate floor. As he tells it, lobbyists for the investor-owned utilities in attendance, didn’t know what hit them.

Sibley called a press conference on the Senate floor, flanked by a lobbyist representing cooperatives and another representing municipally-owned utilities.

“There were some shocked people,” Sibley joked, namely lobbyists representing investor-owned utilities — about 15 of whom were lined up in the back of the Senate chamber.

The day of the press conference, one lobbyist from Houston Lighting & Power told the Austin American-Statesman called the move “a masterful stroke of leadership;” another told the Houston Chronicle it “stings pretty good.”

Tom “Smitty” Smith, then a lobbyist for the environmentally minded consumer-protection nonprofit Public Citizen, said deregulation seemed less a possibility and more of a certainty after that.

“It was kind of like standing on a mountain and kicking a rock and watching it become an avalanche," he said.

Still, there was stiff opposition from large utilities.

Resistance

At the time, Dallas-based Texas Utilities and Houston Lighting & Power controlled 55% of energy generation in the state and stood to lose a lot under this new system.

The Association of Electric Companies of Texas, or AECT, represented the state’s seven largest utilities at the Texas Capitol. The companies had a combined worth of $70 billion in assets, and they spent a fortune in 1997 and 1999 to kill the deregulation efforts.

Tom Baker, who worked at Texas Utilities and spoke in committee on behalf of AECT, likened those large utilities' control of the market share to organic monopolies, arguing that sometimes there’s just dominance within any market.

“For an example, [in] the canned soup industry, the largest competitor has 73% of the market; lightbulbs, 66% of that market. We talked about electricity being a necessity, and I would just point out if we’re talking about necessities, the largest competitor in the beer industry is 48%,” he quipped.

Baker argued the state's plan would unfairly cap the market share of those utilities in a way that could cripple them. More importantly, he noted, the cap from the typically regulation-averse state of Texas would be more stringent than the federal government's limits on market power.

Despite their opposition, the utilities at the bargaining table were aware that SB 7 was going to pass — that the rock, as Smitty from Public Citizen said, had been kicked and the avalanche was coming.

And if the utilities were going to go along with the new market, they had to address so-called stranded costs. Under the new market, inefficient or outdated investments like coal-fired or nuclear power plants had to be paid off, as the utilities saw it. All told, that would cost about $4 billion in costs, according to legislative estimates.

Smitty likened that to “bailing out the big boys.” He called the bill a “Christmas tree” for the utilities — but said he'd ultimately support it if there were benchmarks to bring on more renewable energy.

The AARP and other advocates for older and low-income Texans also threw in their support after insisting that the state set up a plan to assist the poor with their bills.

Ultimately, Texas Utilities and Houston Lighting & Power cut a deal, too.

Still, there were last-minute concerns ahead of the final vote on St. Patrick's Day 1999. Mario Gallegos, the late state senator from Houston, asked Sibley if, under this bill, his constituents “would be receiving the same level of services … when [a] hurricane … or a storm comes in.”

“Senator, I think you can represent that to your constituents without doubt,” Sibley said.

State Sen. Drew Nixon from Carthage implored senators to ask themselves if there would be unintended consequences as a result of the deregulated market.

“Because we’re talking about changing something that every citizen of the state needs to have good, reliable, reasonable-priced access to,” he said. “And I question whether there’s such a big problem with our current system that we need to make that kind of change.”

Nixon’s concerns were not felt by the majority of the Senate, which easily passed Sibley’s bill on an unceremonious voice vote. The bill went on to get amended in the House 69 times and had just one committee hearing before it passed the lower chamber.

Senate Bill 7 became law when Bush signed it in June 1999.

Over the next few years, the state worked toward a transition to the new market. The deals Sibley cut came to fruition or died on the vine.

Utilities got state regulators to back their plan for stranded costs as they busted up their monopolies over the two years that followed.

Smitty and environmental groups saw the share of renewable energy rise in Texas’ grid, and Texas became the nation’s leading generator of wind power.

The state’s fund to help low-income Texans, known as System Benefit Fund, ramped up. Years later, however, it was used to prop up the state’s budget before eventually getting dismantled by lawmakers in 2016.

Enron & Deregulation

While the deregulatory fight in the Texas Capitol in 1999 may have started on Sibley’s cocktail napkin, the less public push for deregulating Texas’ energy market came years prior.

Ken Lay, the CEO of Enron, had been personally lobbying Bush to deregulate Texas’ market for years. He first sent a letter the governor in 1996 ahead of Texas’ first attempt to deregulate.

He sent another letter in 1998 — one that came across Bush’s desk days after the then-governor won re-election and months before the legislative session.

“We hope that you will again actively support efforts to pass a bill restructuring the electric industry in Texas,” Enron CEO Kenneth Lay wrote. “By passing such a bill, your administration would be responsible for providing the citizens of Texas with the equivalent of a tax cut which could immediately amount to $1.7 billion or more annually.”

It wasn’t the first time he’d written Bush about deregulation. He did so in 1996 ahead of the state’s first failed foray, during the 1997 Texas Legislature, into restructuring its electric market.

Lay and Bush had known each other for years. Enron was the largest contributor to both of Bush’s successful gubernatorial bids and, later, his presidential run, donating more than $735,000 over his entire political career.

Enron and its executives spent tens of millions of dollars over the course of the 1990s and early 2000s during the push to deregulate Texas’ market. The Houston-based firm used to be typical oil, natural gas outfit.

The company moved into the energy markets in the early 1990s after federal regulation allowed them to get deregulated. They had the potential to make millions by essentially trading energy like a stock or a bond — and they did.

A major opportunity presented itself a year after Texas passed SB 7, when California’s deregulation plan started showing its cracks.

Those concerns that Sibley had outlined about California's market on a cocktail napkin wreaked havoc on that state's electrical grid over the summer of 2000.

Starting in May, much of the state saw rolling blackouts — 42 hours of outages, all told. A million homes lost power on the worst day.

A drought in Northwest California crippled its hydroelectric capacity, and market rules aimed at reducing pollution made it harder to bring new power plants online. On top of that, natural gas prices were higher than normal, putting energy traders like Enron in a particularly good position to make money off the scarcity.

Alison Silverstein, the former PUC staff member who helped craft Texas’ deregulation plan, said California’s market conditions allowed for Enron to exploit the crisis. After her days at the PUC, she moved on to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission in the Bush administration and help lead an investigation into energy price manipulation over California's crisis.

Silverstein said Enron gamed the market, plain and simple. Enron used strategies like withholding energy trades, creating false scarcity and selling the same energy multiple times, she said.

“I have done my best to black out many of the strategies,” she said, “but there was a bunch of very smart moves that ripped off a lot of people and created scarcity that was bogus and drove up prices and essentially almost cratered the Western market.”

Silverstein said there were plenty of other traders doing the same thing, but Enron's energy traders, she argued, "were the first people to pick up the gun and start firing it."

Ultimately, FERC staff working the investigation, which continued years after the company imploded and its top executives were indicted for fraud, called for Enron to forfeit its entire earnings across the western U.S. market from 1997 to 2003 — $1.6 billion, all told.

The scandal came to a head before Enron’s bankruptcy in December 2001, but the one-time energy giant limped along as it officially transitioned to Texas' deregulated market — and its market manipulation strategies continued.

In the first six months of Texas' retail electrical market, Enron was accused of inflating demand along North Texas transmission lines by pushing more electricity on lines than was needed. The PUC reported Enron exaggerated the demand for power by as much as 500,000% on North Texas lines and 1,000,000% along West Texas lines to inflate the price and manipulate the market.

Texas’ Public Utility Commission fined them $7 million, and, eventually, kicked them out of Texas’ market in January 2002.