People respond to the threat of climate change in different ways. Some ignore it. Some protest policy. Others commit to changing their own personal consumption habits.

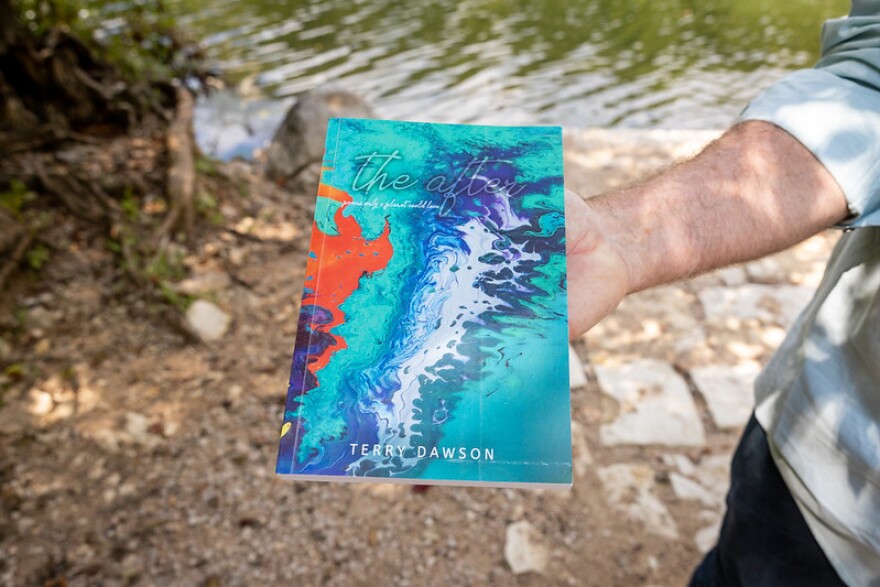

Austin poet Terry Dawson is responding through poetry. He has collected his poems related to the Earth, land, outerspace and the body into a book called The After: Poems Only a Planet Could Love.

Dawson says he wrote these poems at different times. Listen to the interview above or read the transcript below to find out what inspired him and how mortality has influenced his thinking about climate change.

This transcript has been edited lightly for clarity:

KUT: Where did you get the idea to assemble a collection of your poems related to climate change?

Terry Dawson: It actually came from driving in the car and listening to [theoretical physicist] Stephen Hawking talk about the environment and global warming. And he was asked the question, "What is the next step?" And he said, "interplanetary travel." And so I almost braked the car because that was my response. I didn't find my myself giving up the way it sounds Stephen Hawking had. And what I sense that he was suggesting [was] we’re going to save ourselves through technology. And I really reacted to that because I think the ecosystem that we're in and our own mental ecosystem has to change. We are not going to be able to go to another planet and not change. We have to change ourselves here before that.

So that was my motivation to write poetry, which I think gets to a deeper level and allows itself, if people listen to it, to get to a deeper level where the roots are of our tendencies.

You said we need to change our “mental ecosystem.” What did you mean when you said we need to change what's going on mentally in regard to climate change?

We need to think differently. Take stock of the fact that we are in serious trouble and the way the weather has changed so dramatically, and we can see this change. It's measurable change. There's a lot of resistance to that. But I think that resistance comes out of fear. So I don't think feeding the fear is the way to go.

It's falling in love with the planet, I think, is what we need to do. The purpose of our being here is to fall in love with each other and to fall in love with a world that is ours. In my 70th year and seeing my own body starting to fade away, I have my own kind of global warming going on here that it brings it home.

What do you think is effective about poetry and the arts in trying to reach people to be more aware about climate change?

Well, it's how poetry spoke to me, I guess, as a young person. I had great advantage of being exposed to some really high-powered poets as a young person. My high school brought in these people. I could see how urgent their words were to them, and that was contagious. I started to feel that.

In a poem you're going after the more simple, bite-sized pieces to take these bites of reality that we're in. And implicit in that reality is the recognition of how precious and how fragile the world is that we live in.

So you're a poet, you're an author, you're a columnist, you're a Presbyterian minister. What makes you a climate change expert? Folks are probably wondering: Why should I listen to that poetry guy? I'm scared of poetry. I don't understand it. What does he know?

That's a good question. You know, as Presbyterians, as ministers, we are trained to be generalists and not experts. So we know a little about a lot of things. So I only have a bit of the story. You have a bit of the story. We're all feeling the same elephant, and we're all blind and we all see different parts of it. So this is just my bit of the elephant that I'm sharing with you.

I think poetry is the vehicle because pure poetry transcends our reality in a way as I think the mystery of our world transcends reality.

This seems like a good time to actually hear one of your poems. Tell us about the one you're going to read.

It's just called “one.“ You mentioned that I'm a Presbyterian minister. And one of the things about our faiths: We are given a view of how all things work — heaven and hell and those kinds of images — that are pretty simple in our church, schools and our synagogues and our mosques. But as adults, we have to grow into an adult understanding of what it is. And this is my response to that in saying that how we would like things to be is not always how they are. So let's grow up.

“one”

oh, how we want to believe

our being some unique specimen

separate from the rest –

a little above the angels even?

yet what's seen & felt,

what daily dealt out to us like

required doses — like our stingy dreams —

measures out our instructions, namely:

this all around us: all we have

this which comes on breath

famished to consume;

our eternal room awaits no preparation

we've arrived & our home yearns for us —

for our focused love the wonder of our world

resides inside these bodies one with it,

they as whole or particle survive.

Thank you for sharing that with us, Terry. I'm tempted to ask something along the lines of: What does that poem mean? What do you want us to take away from that poem? But poetry seems like a very individual and relational experience, and 10 different people could read and experience that poem and take slightly different meanings and impacts away from it.

Well, that's the wonderful thing about poetry: It's a mirror. It's a reflection of who we are in our diversity and in our diverse understanding. If I may use the poem as a pun, there's not one understanding. Poetry is multivalent. It has many sides.

We're having this conversation at Red Bud Isle Park in Austin. I asked where there was an outdoor spot you might like to meet and have this conversation, and this is the spot you chose. Can you tell us why? If there's something about it that speaks to you, that impacts you?

This place has become a place of calm. But what I remember — my mother-in-law died and I used to bring her here. The older I get, I tear up more. I mean, I am realizing the close of my life by seeing so many lives come to an end around me. And she is one of them. But this was a great place to bring her where she was one who appreciated every leaf — everything she saw — never changed in that regard, and seeing this place through her eyes made it even more special for me.