Volunteers have fanned out in Austin and 12 other U.S. cities this summer to take the temperature of their neighborhoods – literally. The data collection is part of a project to help protect people as the world warms. And, in many places, it is highlighting how already-vulnerable communities suffer the most from climate change and urban heat.

One volunteer, longtime Dove Springs resident Frances Acuña, says she’s noticed her neighborhood has been getting hotter and hotter – and records back her up. In the last couple of decades, long stretches of triple-digit days have become common. Nights aren’t cooling down like they used to, either.

“I was noticing yesterday as soon as I got out, it was like the heat was penetrating into my skin,” Acuña said on a recent August morning.

Like a lot of neighborhoods in Austin, the traditionally Hispanic and working-class neighborhood of Dove Springs was built for the car. Four-lane roads with strip malls and apartment blocks lead commuters off the highway to winding blocks of '70s era single-family homes.

And all that asphalt and concrete, combined with climate change, make heat even worse. They absorb heat, then radiate it back into the air. This phenomenon is known as the urban heat island effect, and even within cities, it can change the temperature by 10 to 15 degrees in a matter of blocks.

It is often lower-income Black and Brown parts of town, like Dove Springs, that are the hottest, because they are likely to have fewer trees and more concrete.

And these areas have the fewest resources to combat heat-related illness. So, for Acuña, a public health advocate, this is an environmental justice issue.

“We have more asthma cases, we have more respiratory infections,” she says. “I believe all this has to do with the heat.”

That’s why she is one of 12 volunteers who agreed to participate in the heat-measuring project in Austin. For one day, she attached a special sensor to the side of her car and drove through the community to make highly detailed heat maps.

Drive Day

“They stick out like … snorkels, I guess you could say,” Marc Coudert, a program manager with Austin’s Office of Sustainability, says about the sensors.

Cities usually use satellites to map hot spots, but satellites measure the ground temperature and not the heat index of the air. So, places like mall parking lots and airports show up hottest on the maps.

“We don’t want to use that as a mechanism to invest in Austin to reduce heat,” Coudert says, “because there are very few people who live at the airport; there are very few people to none who live in malls.”

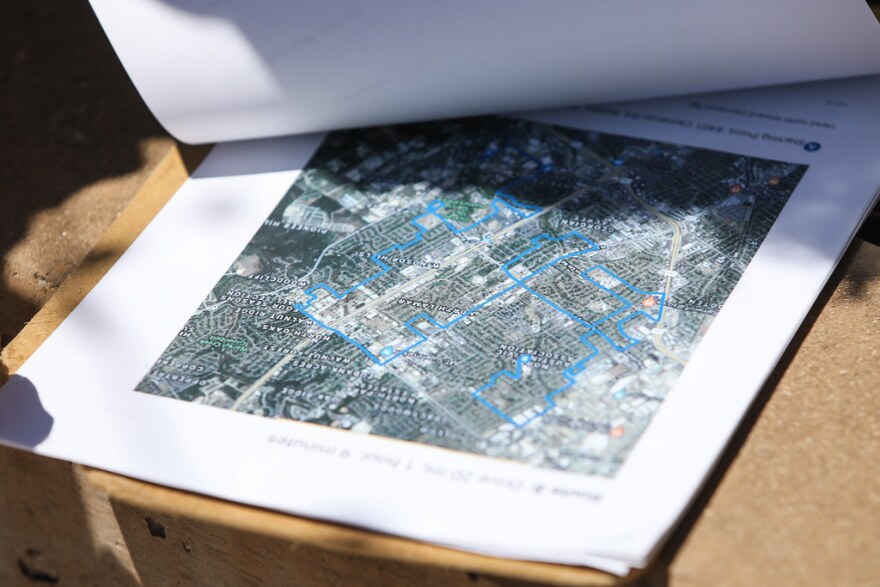

Volunteers drive with the sensors through specially designed routes three times in one day – morning, noon and evening – measuring the heat index where people are more likely to live, work and play.

“The routes are very specific,” Coudert says, and can be confusing.

To make the drive easier, Acuña's friend helps her navigate. As they pass a bus stop with no shade structure, she talks about giving neighbors rides to get them out of the sun. Driving by her child’s school, she mentions how he comes home on hot days dehydrated and “red, completely red.” In an area buzzing with new construction, she says her brother works as a roofer and struggles in the summer sun.

“I think the more you live in this heat … the more resilient people become,” she says. “But at the end of the day, that's where you have years cut from your life.”

Coudert says Acuña’s observations will help as much as the maps themselves in understanding the “true impact” of heat in Austin neighborhoods. After the data is gathered, this type of community input will guide heat-mitigation projects.

Those projects could be simple, like putting in trees, shade structures or more crosswalks to get people out of the sun faster. Or they could be more complicated.

“Maybe it isn’t structure, maybe it’s actually policies,” Coudert says. “Maybe it’s how we set up times that places are open. Maybe it’s understanding how people get to a grocery store from home and have to take two busses instead of one.”

Global Solutions, Local Concerns

The highly localized maps could also advance science on a global scale.

“We don’t really understand fully everything there is to know about urban heat islands yet,” says Hunter Jones, climate and health project manager with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the federal agency that pays for the studies.

Jones says researchers will use the maps to learn how urban heat interacts with climate change and what strategies will work best to combat it.

“It would be interesting to go back and look at some a few years later to see how things have changed both intentionally and unintentionally," he says, "to see how things have developed.”

But the project also reveals how some climate solutions become more complicated when they run up against people’s day-to-day concerns.

Acuña says she likes some of the mitigation plans she’s heard about, but there are also strategies that put residents like her at odds with the city. Residential density is one of them – something she jokingly says she won't shut up about.

Denser development is a key part of reducing greenhouse gas emissions. For the City of Austin, building denser, more walkable neighborhoods is a long-term climate strategy.

But, in neighborhoods like Dove Springs, new development often brings gentrification and displacement, and Acuña worries that it will contribute to increased urban heat and flooding.

“Here it was all green space and everything was beautiful,” she says driving through blocks of new construction. “And now all we see is roofs.”

Instead of denser growth, she wants the city to fund new hike and bike trails along the neighborhood’s greenbelts. That type of green infrastructure is already common in wealthier parts of town and could help people stay cooler and healthier outdoors.

Given how quickly East Austin is changing, though, she also wonders how long people who live in Dove Springs now will be around to enjoy it.

“Every time I see a change, I don't see it for me or for my kids,” she says. “I see it for the newcomers.”

Got a tip? Email Mose Buchele at mbuchele@kut.org. Follow him on Twitter @mosebuchele.

If you found the reporting above valuable, please consider making a donation to support it. Your gift pays for everything you find on KUT.org. Thanks for donating today.