Rotten sandwich meat that’s turned green or black; noodle soup cooked so little that the noodles are still hard; drinking water that smells like chlorine, Clorox or “just bad.” Cramped, cold conditions; tearful separations of children and mothers; guards who said Mexicans won’t ever receive asylum in the United States.

In more than 1,000 pages of new court declarations from children and adults in federal custody, several hundred migrants who crossed the border seeking asylum describe long waits for medical care, outbreaks of chicken pox and untreated diaper rashes. The documents detail minimal access to legal services, with obstacles like language barriers and confusion about their own rights. Some migrants say they are told they aren’t welcome in the United States; others are told it doesn’t matter what they try, they’ll be deported in a matter of days.

Many of these families were separated under the Trump administration’s “zero tolerance” policy, a now walked-back practice of sending parents into federal custody to be criminally charged for illegal border entry while their children were held in federally-run shelters. Migrants gave these statements, which describe conditions in Customs and Border Patrol processing facilities as well as Immigrations and Customs Enforcement detention centers, to lawyers from various advocacy organizations in June and July 2018. Lawyers advocating for the migrants submitted the documents to a federal judge, alleging that the legal requirements for children’s care are being violated and asking that a special monitor be appointed to oversee the facilities.

Federal officials declined to comment on the pending litigation, but cited a June 2018 court document from the government in which Henry Moak, chief accountability officer for Customs and Border Patrol, said that based on his own interviews with children in federal custody, CBP continues to comply with legal requirements for kids’ treatment in those centers. Those facilities are required to provide age-appropriate food and keep rooms at a certain temperature.

Migrant families passing through detention facilities have long complained of such conditions, but new attention — and new duress — have been placed on these families under the administration’s new practice of separating families.

Complaints of cold facilities, inedible food and long wait times were ubiquitous throughout the accounts. Here are some of the most striking stories:

Denia M., a 20-year-old mother from Honduras, crossed the border with her 1-year-old daughter, Zoe. She said she fled after gangs killed her husband and burned down their store in Atlantida; they fled so quickly she said she would miss her husband’s funeral. In detention, her infant daughter got sick and began having diarrhea, but Denia said “I don’t want to ask for a doctor because I am afraid the officials will retaliate and hurt my case if I do."

Manuel A., a 17-year-old from Roatan, Honduras, said he left because of threats from drug dealers. It took him six months to reach the border, he said. Now, he feels “very lonely” and said agents told him his asylum case would not be accepted because “they don’t want stupid people like me here bothering their country."

Katharine B., a 17-year-old from El Salvador, describes saying goodbye to her mother after they crossed the Rio Grande in a raft. Before separating them, an officer asked, "Did you get a chance to say goodbye to your mom?”

Later, Katharine says there is an unattended 2-year-old baby named Bethany in her “cage.”

Rebecca Y., a 21-year-old from Comayagua, Honduras, describes being separated from her 4-year-old niece, Brittany: “They left my niece sleeping in the cell. They didn’t tell me why they had pulled me out of whether I would go back to the cell.”

10-year-old Dixiana S., of Honduras, says she was separated from her mother at a processing facility and put in a cell with other girls. There, “a male officer kicked me to wake me up. … The kick scared me and hurt.” She says all the girls in her cell were crying, and the lights were always on.

A 29-year-old Honduran mother, Dixia S., said she was separated from her 10-year-old daughter despite concerns about her daughter’s asthma. They were placed in different parts of the same facility. “I missed my daughter desperately,” she said.

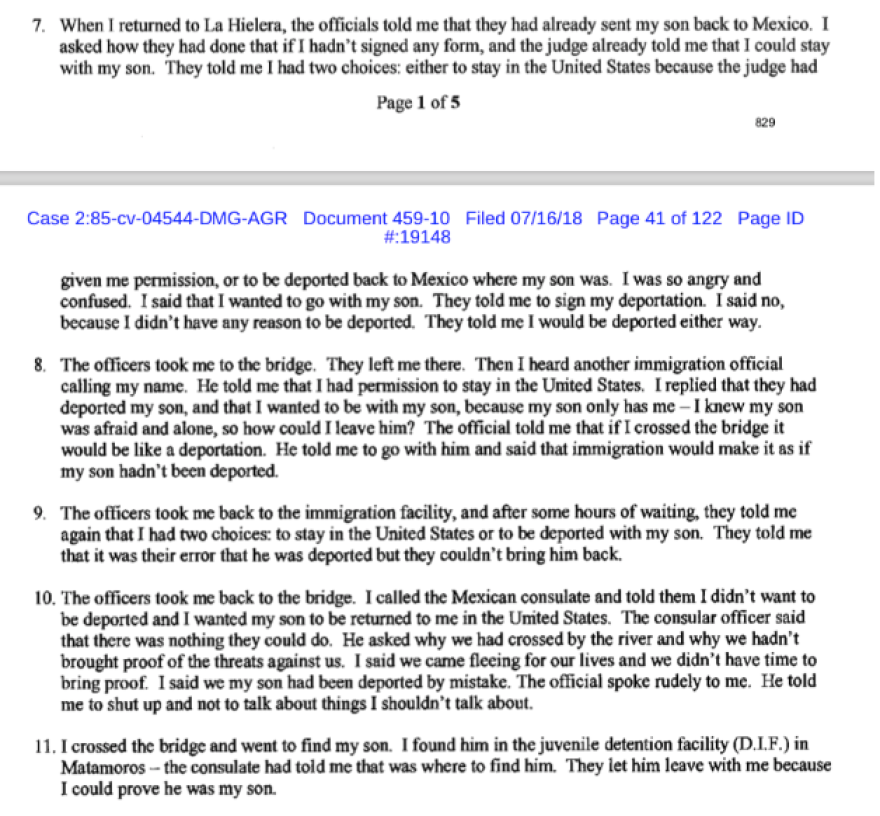

A Mexican mother and son — Patricia H., 43, and Angel A., 13 — each described to a lawyer their journey into the United States, during which they were separated twice.

During their first separation, in Brownsville, Patricia “asked why they had put me in one cell and him in another. They told me that the zero tolerance policy had started, and that they were going to separate mothers from their children. They told me I was going to court.”

Patricia said she told an official that they were seeking asylum. But “he told me that he would put it down in his file but that Mexicans can’t get asylum.”

While Patricia was in court, Angel said he was taken back across the border, handed over to Mexican authorities, and brought to a juvenile detention facility in Matamoros, Mexico. Patricia was told her son had been deported, and that she had the option of staying in the United States or finding him in Mexico.

“They told me that it was their error that he was deported but they couldn’t bring him back,” Patricia said.

Rosa P., a 34-year-old Guatemalan woman, said she was separated from her 16-year-old daughter and could not understand what happened to her during immigration or legal proceedings because there was no one who could translate into her native language of Q’eqchi’, a Mayan language.

Anet M., a 15-year-old from Chiapas, Mexico, says she was told she could not seek asylum “because I am a minor.” Anet is two months pregnant.

________________________________________