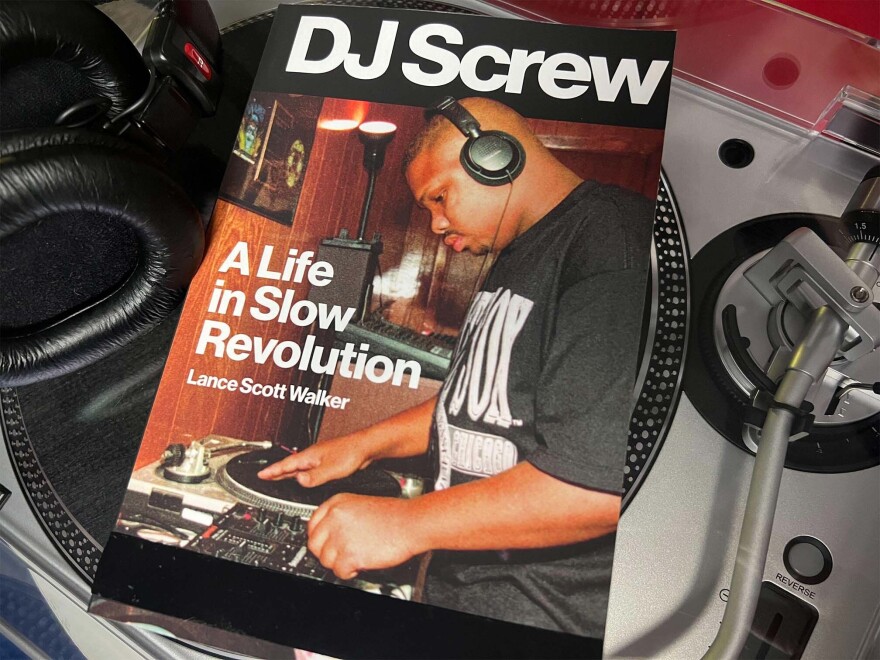

His voice is among the most influential in modern day hip-hop. And now, two decades after Robert Earl Davis Jr.’s death, a new book examines the Houston legend through the people who knew him. The book is called “DJ Screw: A Life in Slow Revolution.”

Author Lance Scott Walker, a self-described white punk rocker from Galveston, talks with Texas Standard about DJ Screw’s style and influences. In the online-exclusive audio above, learn how his family and artist crew, Screwed Up Click, carry on his legacy.

This transcript has been edited lightly for clarity:

Texas Standard: You’ve been researching and writing this book, I understand, for something like 15 years now and previously wrote the book, ‘Houston Rap Tapes.’ But you call yourself in the book, a white punk rocker from Galveston Island. How did the Houston rap scene become such a big part of your life?

Lance Scott Walker: Well, the Houston rap scene is punk rock. The Houston rap scene is an independent scene where, people cut their own path and press up their own records and look after their own careers. And that, to me, is a very punk rock ethic. But the answer to that really is that I’m old friends with the photographer Peter Best. And Peter Best had started a project on Houston rap music in 2004 where he was going to take pictures of Houston rappers and tell the history through photos. And after he’d been working on it a few months, he said, ‘you you’re a writer, you should join me on this project.’ And so that’s how I got started on it. It was a love for for Houston and for Houston music and an awareness of the really great homegrown aspect of Houston hip-hop.

Let’s talk a little bit about DJ Screw. For those who don’t know, why has he left such a lasting impression on hip-hop, not just in Houston, but way beyond?

Well, I think it’s certainly his approach. It’s sort of the mood of the music that that he created. He would take two copies of the same record, put them on the turntables and play one of them a little bit behind the other one. And then at different rhythmic points during the song, he would move from one turntable to the other one where you hear sort of an echo or a repeat of different words or phrases or beats or what have you. Whatever he was hearing, whatever was happening in his head.

But he also would take a body of an instrumental piece and let that run. And then he would pass a microphone around the room and record different people freestyle rapping over those beats. Sometimes they were rappers, sometimes they were just guys that he knew from the neighborhood who wanted to be on the tape. And then they turned into rappers. And then he would take all of that and he would record it. g to cassette. And then when he made a dub of that cassette, a master cassette, he would slow that down with the pitch control. And so the effect that it created was this kind of slow, syrupy, almost psychedelic sound. And that sound just reflected the atmosphere of the city.

A lot of people talk about DJ Screw and they refer to ‘chopped and screwed,” right. Was he the key innovator of that style, that sound, or was he part of a larger sort of community that was all moving in one direction?

He was the key innovator. There were certainly people before him who had slowed records down. There was a DJ in Houston named Darrell Scott who had slowed down songs on some of his mixtapes. As far as hip-hop and funk and that sort of thing, he was the hottest mixtape DJ in Houston through the late ‘70s and all the way through the ‘80s. And he was a big influence on Screw and somewhat of a mentor to Screw.

So he slowed some songs down on some of his tapes and on other ones he did what was called doubling, which is what I explained earlier with the two copies of the same record, which is what Screw turned into chopping.

And so Screw took those two different ideas and put them together and just added his own touch, his own flavor, his own rhythmic accents to the songs.

But I think another part of it, really was that when you had local folks freestyling on those tapes, like I said, whether they were rappers or not, people heard people that they knew, talking about streets that they drove down and neighborhoods that they lived in, and the culture of hip-hop in Houston. And so it really felt like something that belonged to them because they were talking about the city that they lived in.

» Young artists 'chop and screw' rap into new sounds

I think something that may be taken for granted, perhaps because people who have heard his music in the years since is the fact that the music wasn’t dance music, clearly. It was creating a kind of – you said psychedelic – but there was a sort of an atmosphere almost as if when you were listening to DJ Screw, you were sort of surrounded by this sound. Do you know what I’m talking about?

Absolutely. Well, there’s a couple of things at play there. Number one is that we’re going to cassette, and you’re losing a couple of generations when you go to cassette. You’re recording onto a cassette and then you’re taking that and you’re making a master from it. And then you’re taking that and you’re slowing the pitch down in the process, and then you’re taking that master and you’re making dubs from that.

So that’s one part of it. But the other part of it is that on most of those recordings, he’s passing a microphone around the room and the microphone is recording the people freestyle rapping, but it’s also recording what’s coming out of the speakers. So you’re hearing the music. So the music is being recorded direct into a four-track recorder, but it’s also being picked up by the microphone that’s being passed around the room. So there is an atmospheric quality to it that in a ‘real studio,’ the people freestyling would have been in a vocal booth. They would have been isolated, but with Screw’s tapes, they’re right there in the room with them. They’re interacting with each other, I guess.

I wonder, though, if if the DJ Screw sound was more driven by the realities of putting together what he heard in his head, or was this part of it, that lo-fi esthetic that he was consciously creating?

Well, it’s hard to say, because when you go back and you listen to some of the recordings, some of the mixes that he does, there’s really, really super sophisticated movements that he’s making between two very quick spinning records. you get behind a couple of turntables and you think about chopping together different sounds from each of those records, they’re moving really fast. He had to think really fast. And he made a lot of really super precise decisions in those songs, of things that he wanted to run back. OK. I want to repeat this word right here. I want to take this record, rewind it back, or I want to loop this part to where you’re hearing this little instrumental part, and then I’m going to loop it from the next one. I’m going to connect it at exactly that same spot.

So you’ve got that. But then you’ve also got the in the moment kind of lo-fi, live element of the tapes. And I think that’s what makes the Screw tape so exciting, is that you’re hearing someone who’s clearly very skilled at what they’re doing and as a matter of fact, more skilled. I think than a lot of people realize. Because in the end, the Screw tape that you hear is slowed down. But everything that he was doing was in real time and everything that he was doing was a lot faster than the way you’re hearing it. And when you’re hearing that precision, even when something slowed down, you can only imagine how much more precise it had to be at regular speed.

Often you would lose the authenticity or spontaneity in a recording that sort of thought out, but that was present in these tapes. He was very much about being in the moment with the people that were in the room with him.

I guess that’s why he was so committed to Houston. Some people would think, well, you have the kind of success that DJ Screw did. Why not move to, say, New York or LA, where you already had some established scenes? But in a way, he was integral to that growth of the Houston sound, which was its own thing. And I guess part of it was that sense of place.

It was the sense of place and it was the sense of the family that he had built around him, both his family that he’s related to and the family of friends that he created around him. He felt comfortable working in that space. And once things picked up for him, there was there was no need for him to sell off what he was doing to a record label or to a manager or anything like that. He was making plenty of money doing what he loved. And I think that he was smart enough and knew enough about the industry to know that everything comes with a price. And so if you take yourself out of Houston and you go to New York, there’s a lot of compromises that you have to make. And I don’t think that he was interested in that. I think that he had enough space to innovate and to experiment and to do what he really loved within the framework in which he worked. He was never seduced by that. There were definitely labels that tried to sign him, but it never felt like the right thing to do for him. Who knows how that may have changed had he lived and, his career would have certainly developed and changed as the Internet, became more of a force around the world and a way of connecting us. But he never saw the need.

What might have been right had his life not been cut short?

Well, he was such an innovator. He worked in a very analog format. He worked with vinyl and cassettes. He had no use for CDs. They weren’t long enough. In the 1990s, CDs are 70 minutes at the max. So that wasn’t long enough for him. He couldn’t do what he wanted to do with those.

He wasn’t necessarily against technology. He had all kinds of processors and everything like that that helped him create the sound that he wanted. But he was a little slower to adopt technology, I think, than maybe some people are nowadays. We’re used to new technologies coming out. Everybody sort of jumps on them. But I think he sort of laid in wait in a sense. So, wow, who knows? Who knows what he would have done if he was still here and how he would have adapted new technologies and how his sort of idiosyncratic way of thinking about DJ’ing and music, how he would have adapted that to the new technologies.

In the years since his passing, he was named by the governor and an official Texas Music Pioneer. And like his album, ‘Three in the Morning, Part two’ is considered one of the greatest rap albums of all time. If you fast forward to today and what you know about the rap scene in Houston currently. Do you still hear that sound? Do you still hear the legacy? How much does it live on?

It very much lives on because the people, that I was talking about earlier, who were rappers and freestylers on the tapes who may have not necessarily been orienting themselves towards a rap career – some of them now have full on rap careers and have had multiple albums over decades now. And you can still hear that style, the sort of style of rapping that that developed on Screw tapes over the years.

And he’s still got artists like Lil Kiki and Big Pokey and Xero and, all kinds of artists from the Screwed Up Clique that are still making records, that are still relevant and still out there. And people like Trae the Truth are out there is a big part of the community,

Screwed Up Records and Tapes is still open. For 22 years since his death, they only sell his records. They sell CDs, which we think nobody buys anymore, but they obviously do. That’s a hub for the culture right there. But I think that the support that people show for the artists who were on Screw tapes back in the nineties and are now our album artists with their own careers and their own direction that still paid tribute to Screw. He’s very much alive everywhere in Houston.

You said something really intriguing about his sense of family, and not just the family he grew up with, but the he extended community. As you went and tried to to talk to some of the folks who knew him, were you surprised by anything that you learned in the course of those conversations?

Oh, I was surprised by plenty. Yeah, because, Screw didn’t have a, a record label in the traditional sense. He wasn’t marketed. So there was a lot of him that really wasn’t put out there. He did a few it did a few interviews in his lifetime, but really only a handful. And so the stories that people told about him and his sense of humor and his way of making people feel like they were his best friend. Those stories just came up over and over again. So many people told me that they just felt so close to him and he made them feel so special. And that was what made me want to do the book, because I just felt like this was a really special person who connected with people on a profound level and in a way that makes them still want to keep his legacy alive now. And so in that sense, I was fortunate because there were plenty of people who were very enthusiastic to talk about him and to tell that story, because they’d been waiting forever. But his love for the people around him and their love for him, I think, is still omnipresent in Houston today. And that was why I wanted to make the book.

Did you spot a place where it was sort of like a turning point for him that made DJ Screw who he was? What was the transition to DJ Screw?

There’s an early point where he saw the film ‘Breakin,’ in 1984 when he was 13 years old. And he saw Ice-T DJ in that film. And he I said, ‘man, I can do that.’ And that was the point where, he really knew that’s what he wanted to do with himself. And it wasn’t really long after that that, Shorty Mac named him DJ Screw, or asked him, ‘What is your name? Deejay Screw? I like that.’

But I would I would jump forward many years beyond that to the point in at the end of 1993, when he and his girlfriend Nikki moved out of Screws father’s apartment and Screw got his own house at that point, where he could really work around the clock and have the freedom of having people over and wasn’t bound by his father’s rules. So I think really at that point was when he things really clicked and there were no longer any limits on what he could do and he could really fulfill his vision. And that’s when the Screw tapes that we know now really started to happen, because he could really take the time to record and, really make something special with each recording.

Did you feel like in the course of putting together this book, that the book itself sort of evolved?

In the beginning, all I wanted to do was build a library of interviews. I knew that the story hadn’t been told in full. I knew that there were little parts of it here and there. And, of course, there was a Wikipedia page and there were some things out about him. But I knew that if I wanted to tell the real story, that I needed to not worry about necessarily telling the story to myself early on, but to just continue to build a library and let that library tell me the story. And so it definitely evolved. And my first two books were just straight oral histories, culled from all my own interviews. But, in the end, it’s really just the interviewees speaking. So I wanted this book to be something, between that where I, I’m the writer, I’m your narrator, I’m your guide. I’m going to take you through this, but I’m going to pass the microphone around and I’m going to let people talk at length because I really want their voices to be the ones that tell the stories. And, so I built I took time over the years to build up a library of interviews and then go through and find stories within those interviews that I thought, number one, were informative, but number two were good stories. And, there’s so many great storytellers in the book who just have a great natural rhythm to their way of speaking and their way of telling stories and being generous with facts and events and that sort of thing. So it definitely evolved over the years because it evolved into something where the format that ended up being, which is a hybrid narrative oral history format that I’ve never seen anywhere else.

Was there someone that you spoke with that struck you as especially close that they gave you information that that sort of seemed to anchor a lot of the DJ screw story?

Shorty Mac, his cousin from Smithville, Texas, who was also his best friend when he was in Smithville. And he was crucial throughout the process. He was one of the most accessible people for me over the years. I got to know him really well. And he was able to really fill in some gaps of information that I didn’t know because he was there in Smithville growing up with him. And then he also came to Houston and he worked at Screwed Up Records and Tapes. And so he was there for so many different parts of his life. And then, of course, his family were the true anchor – his sister Michelle and his nieces and his nephew and everybody else and his cousins were all just a huge help and really anchored to the kind of mix of his blood family and then also the family that he built around himself over the years.

You talk about his kinfolk. How much of an influence do you think they had on him?

Oh, they’re a huge influence on him. because, his mother in particular was really big on music and would play records around the house all the time, and made tapes for friends of hers. And I think that that was a massive influence on him. And the proof is in listening to some of his Screw tapes over the years. There are R&B songs on there. There are all kind of funk songs on there, some blues that were straight from his mother’s record collection. So I think Screw picked up influences from all the people that were around him because he connected so closely with everybody. And you just can’t help that if you’re close with the people around you, you’re going to be influenced by them. He has so many wonderful people in his life growing up that I think he was influenced by all of them. But I would say that his mother was was a massive musical influence on him.

When someone says, 'How should DJ Screw be remembered? What’s his legacy?' What do you say?

Chopped and Screwed. There’s a distinction between his style and his influence on hip-hop in general and the greater mainstream. Chopped and Screwed refers to his work – the Screwed part in particular, or Screwed music or Screw tapes – that’s referring to him. But other DJs have their take on it now, whether it’s slowed and chopped or chopped, not sloppy, people have different ways of referring to it. But I think that he has created a genuine art form, a genuine way of thinking about music from the top. A lot of times people do remixes and they’ll get all the separate tracks. They’ll get a track with the drums, they’ll get a track with the bass and the vocals. Screw didn’t really work like that. Screw was taking a preexisting recording and figuring out a way to cut into it and kind of tear it open and show you different parts of a song and maybe repeat parts of it so that you really understood that, hey, this is something I want you to hear. And I think that his is his influence going forward will be more than just music and more than just DJ’ing. I think it’s more about how you approach an art form, whatever that discipline might be.

If you found the reporting above valuable, please consider making a donation to support it here. Your gift helps pay for everything you find on texasstandard.org and KUT.org. Thanks for donating today.