Camera technology has improved dramatically in the past decades, but one thing about even the newest cameras has stayed constant: They all have lenses.

Now, that's changing.

Engineers in Texas are building a camera that can make a sharp image with no lens at all.

Why would you want such a camera? Richard Baraniuk, a professor of computer and electrical engineering at Rice University, says lenses make a camera bulky. He and his colleagues wanted to build a camera that could fit into spaces where traditional cameras could never go.

To design their camera, Baraniuk and his colleagues looked to the past for inspiration.

"Back to really the very first cameras, pinhole cameras," Baraniuk says.

Pinhole cameras have been here for quite a while. According to some scholars, they were first described by the Chinese philosopher Mo Ti around 400 B.C. These cameras later came to be known as the camera obscura. Light enters through a small hole into a darkened space, sometimes as large as a room, and an image of what the hole was pointed at appears on a screen.

With the invention of film and later photo sensors, it became possible to capture that screen image.

"The disadvantage of a pinhole camera is that while it provides the simplicity of interpretation of the image, it lets very little light through," Baraniuk says. "So it's very inefficient that way. It's a pinhole after all."

So he and his colleagues decided to build a camera based not around a single pinhole like you might build for a science fair project, "but one with literally millions of pinholes," Baraniuk says.

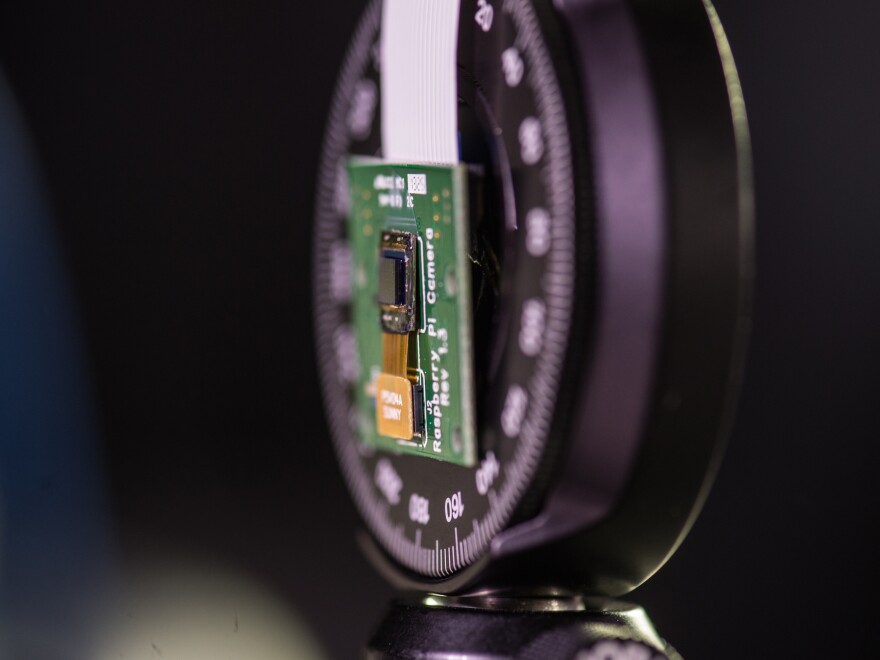

These millions of pinholes in Baraniuk's camera are really tiny, so you can pack a lot of them together on a thin piece of plastic. Lay the plastic down over a semiconductor chip that's sensitive to light, and voila: You've got a camera that's almost completely flat.

But there's a problem. A million pinholes produce a million images, all smeared on top of one another.

How to separate them?

Ashok Veeraraghavan, an assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering at Rice, says the answer is computation. Lots of digital cameras use computation to improve the quality of the image created by the lens in a traditional camera.

"The entire community of computational imaging has started recognizing that computation can not only be used to improve images that have been captured by the earlier camera designs, but actually change these camera designs in radical fashions," Veeraraghavan says.

Such as a camera made from a million pinholes.

Veeraraghavan says it's possible to computationally "unsmear" those million images from those million pinholes to make a single sharp image of what the camera is pointed at. For details on how it's done, you can see this paper.

Baraniuk agrees their work will radically change camera design.

"You could imagine making, for example, wallpaper that you could paper over a wall to create an extremely massive camera," he says.

Using an entire wall as a camera means you could see absolutely everything in the room, including things that would be out of sight or distorted in a single, smaller camera.

Or build a cylindrical camera, put something in the middle of the cylinder, and you can take pictures of it from every angle at the same time.

Right now the images his FlatCam can produce are about as good as the first conventional digital cameras, but Baraniuk expects they'll get better very soon. He expects people will come up with ways to use the new camera that he can't even imagine yet.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDA3MzEzNjc2MDEzMDI2Mzc4OTc4NTFmNg001))