This story was originally published on July 27, 2016.

One hundred eight years ago, Harper Baylor Lee’s hobby became something more than that.

The 24-year-old worked for the Central Mexican Railroad in Guadalajara, Mexico, where he’d spent most of his life after a move from El Paso. But on a Tuesday in July, after years as an amateur, he started a career in bullfighting and became the first American-born matador.

Lee was born James Harper Gillett in Ysleta in what’s now El Paso in 1884. His father, James, met his mother, Mary Baylor, as a Texas Ranger – Gillett served under her father, Col. George Baylor.

After the two divorced on the grounds of infidelity in 1889, Mary changed her son's name from James Harper to Harper Baylor. She married, was widowed and married again before the family moved to Mexico with railroad engineer Samuel L. Lee in 1899, her new husband who unofficially adopted Lee.

After finishing high school, he trained with a matador and Spanish ex-pat Francisco Gomez, known as "El Chiclanero," according to the extensively-researched 1962 book about Lee, "Knight in the Sun," by Marshall Hail, with illustrations by Texas art luminary Tom Lea.

From him, Lee learned both the traditional, no-frills techniques and the flashy maneuvers, or suertes, of bullfighting great Francisco Montes.

But Lee wasn't known for his technique as much as he was known for his physicality. In that first match (corrida) at the Plaza El Progreso in Guadalajara, he pole-vaulted his second bull, a move which Montes had popularized.

He also performed a move he'd later become renown for – breaking the banderillas, the barbs used to stab bulls, in half before striking a bull between the shoulders. At six-foot, he was taller than most of his contemporaries, so he had an advantage in terms of reach.

But the move which he became most well-known for was his cambio al rodillas – a move in which a matador kneels before a bull, holds his or her cape out in front and then waits until the last second to avert a bull.

In the Mexican press his exploits were initially reported upon as a novelty, but he was later praised as he ascended the ranks of the circuit, from his adoptive hometown of Guadalajara to Juarez to Monterrey to Mexico City. In his hometown, he wasn't as well-received. A parade through El Paso put on by fight organizers was sparsely attended, and his father disowned him after learning of his career decision. They didn't speak until after his retirement in 1914.

But he also drew headlines because of his complete disregard for personal safety. In his career he was gored more than 30 times, two of which were near-fatal affairs.

The first near-fatal goring in 1909 struck him in the groin – or "noble parts," as Hail describes – and required the removal of a testicle. All told, the wound required 147 stitches, was wrapped in 12 yards of gauze and, to prevent blood poisoning, was treated with ether, stychnine and enemas of cognac. His doctor advised him to stay away from bullfighting as he may again suffer a "similar misfortune."

"Well, let's see," Lee said in response. "In that case, I could bill myself as the world's only bullfighting eunuch."

Lee should have been recovering for the better part of six months. But, against the wishes and advice of pretty much everyone he knew, he returned to bullfighting at the Plaza El Progreso in Guadalajara on January 10, 1910. Months later on May 8, 1910, his wound still bandaged, he had his second near-miss.

His last bull threw him. Its horn grazed him and opening up his still-mending wound and, as Hail describes, nearly disemboweling him.

Harper staggered to his feet. He felt a familiar warm trickle down one leg; his breeches were reddening along his thigh. He had no great pain, but there was an uncomfortable protuberance below his beltline. Reaching beneath his torn sash and breeches, he searched for the bandage he still wore over the wound he had received in San Luis Potosi. It took him a moment to realize what had happened: the horn blow had torn open the old wound and part of his intestines were protruding.

Believe it or not, Lee returned to the ring and finished the fight before being carried out of the ring. Many papers, including those in his hometown, initially declared him dead.

Months later, Lee returned to bullfighting, after two Spanish writers suggested to some of Lee's companions that he could be honored as a master matador and fight in Seville, Spain – the highest honor for bullfighters. He returned to the ring in Saltillo. But in October 1911, before a packed house, he was gored directly above his knee, an injury that doctors feared would require amputation.

While his leg eventually healed, he announced his retirement following the match.

"I am not lacking in courage nor in ability to continue," he said in an interview. "But I have a great deal of pride; and you must understand that I am going to retire before the public retires me."

As the Mexican Revolution began, Lee fled to his native Texas and later married his girlfriend Roxa Dunbar, who refused to do so until she got bullfighting out of his system, according to Hail. In a ceremony at his home, Roxa cut off his coleta – the traditional braid worn by bullfighters.

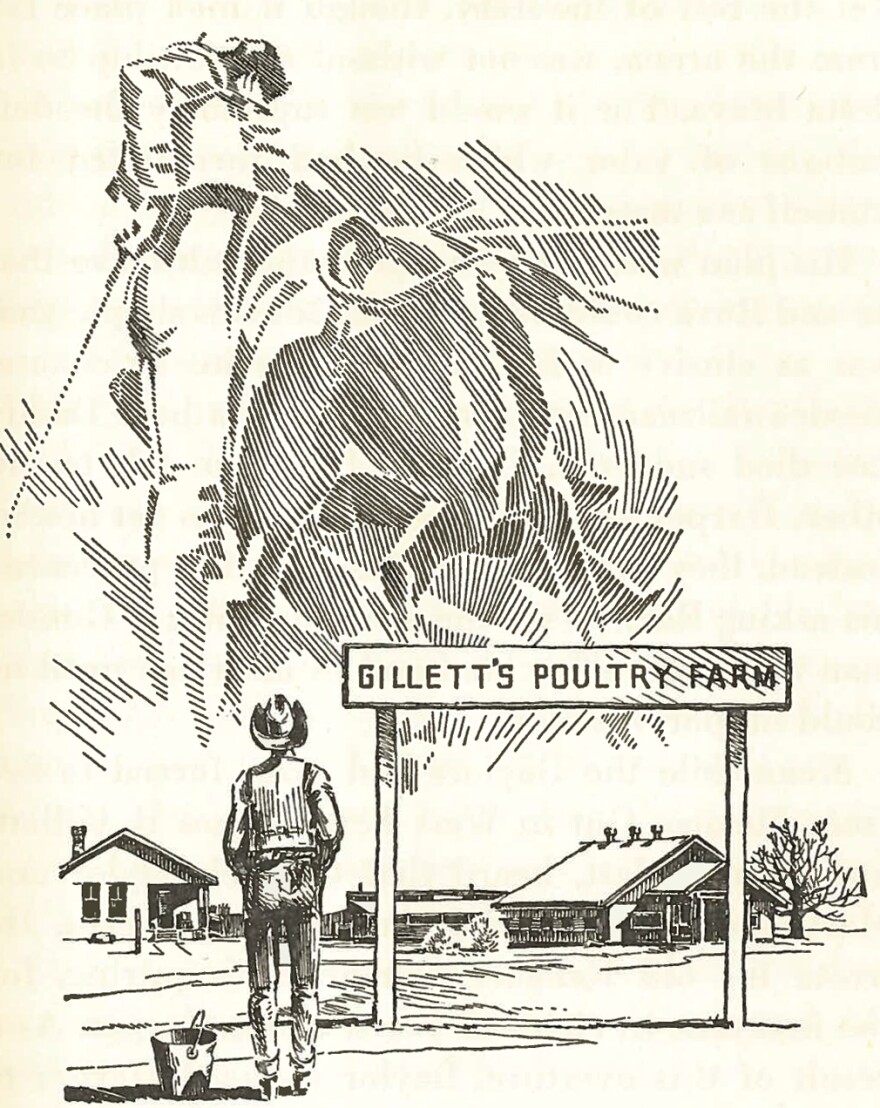

Years later, he reconnected with his father. Their first meeting at the Gunter Hotel in San Antonio proved awkward. Lee's grandfather, his father's former commander, had to reintroduce them, as they didn't recognize each other. They didn't talk about Lee's mother, or his bullfighting, Hail writes. When he married Roxa, he changed his name to Harper Gillett and later started a poultry ranch in San Antonio.

He later passed away from mouth cancer in 1941. His tombstone, Hail notes, features his name and has no epitaph – no mention of his days as a matador.

Further Reading