This story was originally published on Jan. 13, 2016.

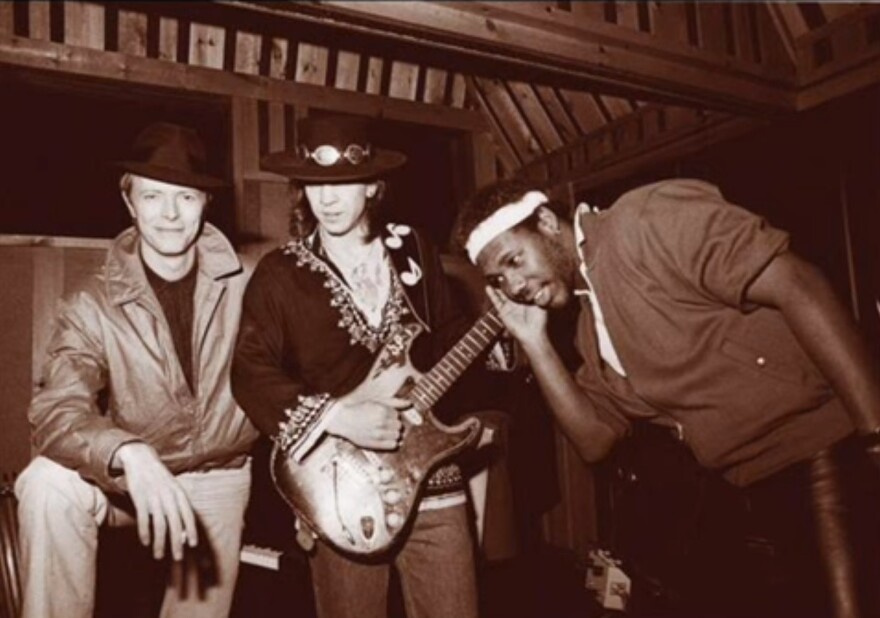

The death of David Bowie has made many an Austinite reflect on the Thin White Duke’s most direct Austin connection: his partnership with Stevie Ray Vaughan that shined an international spotlight on the Austin guitarist. The two met at the Montreaux Jazz Festival in 1982, where Bowie first took a shine to the Austin guitarist despite a less-than-warm reception from the crowd.

Vaughan and Double Trouble were the first ever unsigned act to play the festival and, Layton says, the band nearly exhausted nearly all its shoestring budget getting to Switzerland in the process. On the festival’s first night, the crowd, expecting an acoustic set, booed the band off the stage. It wasn’t the laidback set attendees were promised and they responded accordingly, but Vaughan’s guitar playing did catch the ear of one attendee: David Bowie.

Bowie sent an emissary to the band’s dressing room after the show requesting an audience at the bar frequented by festival performers.

“Oddly enough, Stevie spent just a couple of minutes talking to him, and then he got up and left and never really returned,” Layton says.

Layton stayed. He talked to Bowie for another hour or so, and says the late singer’s interest in the band was piqued and told him Vaughan was the “greatest urban guitar player” he’d ever heard. Bowie’s proposition to both Vaughan and the band was simple: Vaughan would play on his new record he was working on with Chic-alum Nile Rodgers, then Vaughan and Double Trouble would open up for him on the tour that would ensue – Bowie’s first tour in five years.

In the liner notes of a DVD of the Montreux set, Bowie wrote that he took his “courage in his hands” and asked him, but wasn’t expecting much:

“And as Stevie's music was such hard core blues I expected and would have understood a polite ‘thanks, but no thanks.’ You can't imagine how delighted I was when he accepted the offer on the spot and said he'd love to try out a new kind of record just for the experience. When I asked if touring could also be a possibility he again replied in the affirmative, 'Hell, yeah,’ he said, ‘I tour real good.’”

The next night, the band played another show to a much more receptive crowd, which included another musical luminary: Jackson Browne. Vaughan and Double Trouble played with Browne and others all night and after the session ended at sunset, Browne offered the band as much studio time as they needed.

In December of 1982, Rodgers and Bowie completed recording of “Let’s Dance,” and Vaughan flew into New York to overdub lead guitar over the tracks and, as Bowie wrote, “rip-up everything one thought about dance records" and dedicated his solo on the title track to bluesman Albert King.

Because Vaughan and Double Trouble’s base of operations was in Austin, Bowie decided to meet them halfway for the tour preparation by locating the April 1983 rehearsals at a Las Colinas soundstage near Dallas ahead of the first show in Brussels in May.

Still, Layton says, Vaughan wasn’t 100 percent committed to the whole arrangement. Double Trouble had taken up Browne on his offer to record in November of 1982, just before Vaughan went to record “Let’s Dance,” and the recordings ended up comprising the band’s debut record “Texas Flood.”

Staring down the barrel of what the band thought could be a multi-year worldwide tour, Vaughan began to second guess the Bowie tour and so did his bandmates Layton and bassist Tommy Shannon.

“We actually told him, ‘You know, this is ridiculous. You can’t do that,’” Layton says. “And all along Tommy Shannon and myself were thinking could that even be real? Could we even expect that, you know, two or three years from now that we could even be a band again?”

Bowie’s management dropped Double Trouble as the opening act just before the tour, and both camps were at loggerheads over Vaughan's touring fee, giving Vaughan pause as he headed into the final stretch of rehearsals.

“They wanted all personal and career publicity…any of that activity to be orchestrated by the Bowie camp,” Layton says. “It was kind of a last minute addendum to the deal – was that he couldn’t say anything about himself or his career unless David Bowie approved it, and that’s when he decided to leave.”

At the last second, Bowie replaced Vaughan with Earl Slick, who learned the nearly 30-song set in 72 hours before the first show in Brussels, and the 96-show world tour lasted seven months. “Let’s Dance” became Bowie’s best-selling record, while the recordings of the rehearsals became a much-coveted bootleg known as “Dallas Moonlight.”

Vaughan and Double Trouble released “Texas Flood” in June of 1983 to both critical and crossover commercial success, peaking at No. 38 on the Billboard 200. Still, while it was a solid breakout debut for the band, it didn’t net Vaughan and Double Trouble their first Grammy. Ironically, it was a record that included that first Montreux show and another follow-up set in 1985 – after the band had garnered international cache – during which they weren’t booed off the stage.

Layton says Vaughan got the exposure that he wanted out of the partnership, but that there were two things Bowie didn’t understand about Vaughan: that he didn’t like to be controlled, and he wanted to get Double Trouble off the ground.

“Stevie had said the only thing that he ever wanted to do was have a band and make his own music,” Layton says. “I think he was in conflict about the whole thing from the beginning because he was trying to figure out how to keep us fed and take care of us.”

While Vaughan had some choice words about the ordeal in 1986, the two ultimately made up after running into one another on tour and bonded over Stevie’s new-found sobriety just before Vaughan’s death in 1990.

Below you can listen to the entire (relatively) uncut conversation with Double Trouble drummer Chris Layton.