This story is part of Episode 7 of "Sugar Land." Listen to the full episode above. First time here? Start with Episode 1.

It’s a made-for-Hollywood story: An enslaved man, once forced to dress and serve his white master on the swampy shores of Galveston Island during the Civil War, is emancipated. He goes on to become one of the first Black educators in Texas and helps start schools for freedmen across the state. But he can’t escape the risk that comes with being Black in the South. At 30, he’s arrested and sentenced to work for another white man under Texas’ oppressive convict system. He never regains his freedom.

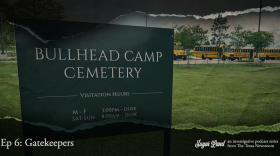

The dramatic twists and turns of Watt Bonner’s life read like a Shakespearean tragedy. And his story is one you’ve likely never heard before. Until now, it was buried among the Sugar Land 95 — on the side of a school, in a misnamed cemetery.

Had we not noticed the cracks in the official Sugar Land 95 narrative endorsed by the Texas Historical Commission, Fort Bend ISD and Principal Research Group, his story would still be lost.

Finding Watt Bonner

Back in the spring of 2021, we had spent the morning searching for information about a man on PRG’s original list of convicts named William Bonner, who was convicted of theft in Bastrop County in 1879. But, we came up empty. Later that night, we were researching a different name on the list, John Norton.

Norton was also convicted in Bastrop County in 1879. According to news reports we found, Norton and another Black man were accused of stabbing a Bastrop County sheriff’s deputy when he was trying to arrest a, quote, “negro gambler.” All three of the Black men involved were arrested and jailed. The local newspaper listed Norton as one of 13 people being held in the county jail on this particular day in February 1879.

“My God, this man, he's a hero. He's truly a hero for education.” — genealogist Franklin Smith

And, running down that list, another name caught our eye — Watt Bonner.

We went back to the list in PRG’s report and saw that William Bonner was transferred to the prison on the same day as John Norton. They were sent to the same camp and their convict numbers were only four digits apart. That means they were processed around the same time.

William and Watt? They had to be the same man.

A deep dive into state archives eventually revealed a total of seven documents containing Mr. Bonner’s name. In four, he is simply referred to as W. Bonner. In two he is either "Mat" or "Wat Bonner" with one T. In another, he is "Matt" or "Watt Bonner" with two T’s. Cursive W’s at that time look a lot like M’s so that could be where the discrepancy comes from. Regardless, the name William appears nowhere we could find.

If we’d taken PRG’s report and the quality of the Texas Historical Commission’s review for historical accuracy at face value, we would have never discovered the truly remarkable American story of Watt Bonner.

Watt’s early life

Watt was born into slavery in Alabama in the late 1840s, and moved to Freestone County, Texas with his enslavers when he was still very young. We refer to his enslavers as the White Bonners. They were an Irish family who immigrated to the U.S. in the 1760’s and eventually made their way to Texas. They were known for being highly educated, in fact, three of the five White Bonner brothers were doctors. But they made their real money in agriculture.

To date, we’ve only found one physical document that offers any definitive proof that Watt was enslaved by the White Bonners in Freestone County. It’s a letter dated May 29, 1864, and it reads, in part, “The military authorities have seized Irvin B's boy Wat. He was one of the Bonner negroes who first ran away from here.”

While this may not look like much on its face, it’s significant. First, we know "Irvin B" is Irvine Bonner, the youngest son of one of the wealthy White Bonner brothers. In 1864, Irvine and his cousin “Mac” Bonner were soldiers in the Confederate Army. That spring, they met up with other soldiers from Freestone County who were stationed in Texas–including Mac’s uncle, Dr. Thomas B. Grayson. Dr. Grayson sent dozens of letters to his wife during the war, including the one that mentions Watt.

We know from the letters that Irvine and Mac Bonner traveled south with Grayson’s company to Galveston, where Grayson sent his May 29th letter. They were stationed there to make sure the Union didn’t take control of the port. Wealthy Confederate soldiers often brought one or more of their slaves with them to cook, clean, set up camp, dress them and do whatever else needed doing while they were away from home.

While the White Bonners weren’t seeing much, if any, action in Galveston, the Black Bonners, including Watt, were likely kept quite busy — put to work building up the island’s defenses. They built forts, laid rail lines and erected a huge wall of sand along the island’s perimeter for extra protection.

Looking back at our original letter, it seems at some point while they were in Galveston, Watt tried to escape and was captured. Local history buff Andy Hall told us that likely meant trying to get to the Union ships stationed just off the coast.

“Galveston is an island. You're not going very far, with one exception. You get a boat, and you get out to the Union fleet, which is 500 yards off that way,” Hall said. “There were Confederate soldiers who tried to do that…If Watt was trying to escape, he must have, I would guess, he was trying to escape to the blockading fleet, which — if he could get hold of a boat — would not have been difficult to do.”

The military authorities Dr. Grayson says captured Watt must’ve been the Confederates because Galveston was under martial law at the time. We’ve searched and searched, but we can’t find any record of Watt’s imprisonment in Galveston. Hall thinks he was probably just released back to Irvine Bonner, but we can’t know for sure.

What we do know is that just over a year after Watt’s escape attempt, Union general Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston with General Order Number 3 in hand. It read, “The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free.” That day is now commemorated as Juneteenth.

We wondered if there was any chance Watt was still in Galveston then. Maybe he was forced to keep building up the island’s defenses. Either way, for years, Watt had a front row seat to the battle over his freedom and was forced to watch it play out from the wrong side.

From slave to teacher

When the Civil War came to an end, the federal government established the Freedmen’s Bureau to help formerly enslaved people transition into free society. One of its major contributions was the establishment of schools for newly freed Black children and adults.

One night early in our search for Watt Bonner, we came across his name in a batch of Freedmen’s Bureau records. It was at the bottom of a report that showed how many students were enrolled in a Grimes County school that month. Watt had signed the report in curly cursive next to his title: Teacher.

Further research revealed dozens of school reports containing Watt’s name. Perhaps the best is this letter from November 1868, which Watt sent to the man in charge of Freedmen’s Bureau schools in Texas:

To Mr. Joseph Welch,

Sir, I am the said Watt Bonner. I have been a regular schoolteacher for freedmen and refugees in the said state of Texas for the last 3 years, and now I wishes very much to bring my school under the rule of the government. It is said by the most of our school agents who have visit our schools in time past, that I had the discipline of the best school system that they ever seen taught for freedmen in the State of Texas.

I am a colored gentleman,

Watt Bonner is my name,

and to educate the children,

have always been my aim.

I am in great hopes that you will ordain and license me as a regular government school sergeant. I will thank you more than much to forward me an immediate reply and send the license with the answer.

I remain your most obedient servant, Watt Bonner.

We used this and the other records to map out a timeline of Watt’s career as a teacher. Texas’ first Freedmen's school opened in Galveston in September 1865, and within four months, Watt had landed his first teaching job in Houston. The records suggest Watt had a brother named Henderson Bonner, who taught with him in Houston, too.

It was often hard to find any information about the men who could be among the Sugar Land 95 — No family, no tax records, no mentions in the newspaper. This was so far beyond what we thought was possible to uncover. We had these three Watt Bonners: the slave, the teacher and eventually, the convict, each with his own tangible, individual identity.

We had to know if our three Watt Bonners were one and the same. So, we brought everything we’d found to Franklin Smith, a professional genealogist who worked for years at the Clayton Library Center for Genealogical Research in Houston. He’s retired now, but he agreed to help us look into Watt’s past.

“The circumstantial proof indicates and clearly supports, to me, that he is the same Watt Bonner that was the teacher,” Smith told us as he went through our research.

That’s the phrase Smith kept using: “circumstantial proof.”

“The accumulation of evidence points in that direction,” Smith said. “What you would have to do is try to disprove it.”

Smith marveled at Watt’s willingness to venture out of a big urban hub like Houston and teach at schools in more rural counties.

“Venturing out in a place like Colorado County or Grimes…that would have taken a lot of courage at that time,” Smith said. “You had these white folks that were still bitter and angry. And to find a Black man that could read and write that had formerly been enslaved in Texas...They wouldn't have wanted him to educate the local black people.”

The Freedmen’s Bureau records contain tons of letters from teachers at schools across the south detailing the violence they and their students faced on a regular basis. In 1871, a man in Bastrop claimed the KKK showed up at his door while out hunting for Black teachers.

In Tyler in 1868, when a group of Black children refused to move off of a sidewalk so white people could pass, the white people of the town spent the next two days beating the children with clubs and stones as they walked to school. Their teacher suspended classes; afraid the kids were going to be killed. The Texas’ superintendent of education adopted a policy that pushed for Bureau schools to be opened only in towns guarded or reachable by federal troops.

All of which just makes Watt’s career even more impressive.

“He's starting these schools. He's getting these schools off the ground. He's excited about it, you know, and he's dedicated,” Smith said. “My God, this man, he's a hero. He's truly a hero for education.”

And he really was. In the five years after slavery ended, Watt taught at five different schools across Southeast Texas. The last time his name appears in the Freedmen’s Bureau records was in January of 1870, when he filed a report from a new school he successfully opened in Navasota. The Bureau ceased operations in Texas six months later, and then we lose track of Watt for a long time.

Watt enters the convict lease system

Watt Bonner’s story picks up again nearly a decade later. In the years in between, we don’t know where he was living or who he lived with. We don’t know if he continued teaching somewhere else, or if he had a job at all.

What we do know is that a man named Watt Bonner was in the Bastrop County jail in February 1879.

Watt’s alleged crime was theft, but we don’t know what he was accused of stealing or from whom. We don’t know if he had a lawyer or a trial or if he tried to appeal the verdict. Just that he was convicted and sentenced to seven years in the state penitentiary. Watt was sent to J.D. Freeman’s plantation in Sugar Land, becoming one of 40 incarcerated men working there at the time.

After he first arrived, records show he managed to escape, but was recaptured later that month. Watt was described as a 30-year-old Black man, 5-feet-8-inches and weighing 160 pounds. Even though detailed records on the conditions of J.D. Freeman’s Camp are sparse, it seems pretty on par with the other convict camps in the area: hot, humid and miserable.

Many of the prisoner deaths on Sugar Land farms are attributed to malaria, sunstroke and even some drownings in the flood-prone Brazos River.

As one camp inspector wrote at the time, “I have found that during the months of July and August, it has rained almost every day. The men have consequently been frequently wet, sometimes two or three times a day. There has been, of course, a great deal of sickness on most of the farms, principally chills and fever.”

According to Watt’s prison records, he survived only two and half years of his seven-year sentence.

He came down with pneumonia and died the day before New Year’s Eve in 1881.

The other convicts likely built him a coffin out of rough pine and lowered his body into the ground while the guard stood watch. His family, if he had any, probably would not have been notified. His name and his convict number might have been written on a wooden headstone, but that’s long gone now.

And with it, his whole remarkable life story was erased.