Damaris Covarrubias lives in Dove Springs, with her entire extended family. It is a huge family. So large in fact, that Damaris has never stopped to actually count how many there are.

“Okay, my grandparents, I think they had 9 kids. Cousins? I think there’s like 30 or 40 of us. Including the little ones? I don’t know. And now every cousin’s having babies so it keeps on growing and growing,” Covarrubias admits.

The vast majority of her cousins have become parents while they were still in their teens, and that’s pretty typical for Dove Springs.

In 2008, when Damaris was 12, KUT interviewed two of her cousins, Jessica and Marlene.

At the time, both were 19, and both were already mothers. Marlene had just delivered her third child. Back then, Jessica said her biggest influence was her surroundings.

“If you see a Hispanic family versus a Anglo family, all their kids are in college and stuff and you see that generation by generation," Jessica Covarrubias says. "And, in our generations, everybody has kids.”

Damaris grew up the same way as Jessica – watching her cousins rearing children. Now she’s 18. Looking back – she says didn’t like the status quo.

“I would look at them and I would be like, ‘No, I don’t want to be like them. I don’t want to go through the same things they are going through.'”

As she talks, a little girl with long dark curls walks up. Damaris is now a mother. And, just as she experienced with her cousins, her life is tough.

“I’m still a full-time student and I am working full-time too," she says.

Damaris says she could never do all that she does if it weren’t for her support system. After her divorce this past December, she moved back in with her parents so they can care for Dalilah, her 2 year-old, while she pursues a career in nursing.

Jordan Nicquette is a Physician Assistant in Dove Springs. She says, in this neighborhood, many families are like the Covarrubias, where three or four generations band together to raise children.

"Which is kind of a neat cultural phenomenon because, in other ethnic groups, it’s just them – maybe [they are] outcasted for it," Nicquette says. "But you definitely don’t see that in the Hispanic community. They all go 'We are all going to help.' This is now our either problem, or joy.”

Whether it is a problem or a joy – teen births have huge social consequences that are pretty evident to Leonora Vargas, the director of the Family Resource Center at Mendez Middle School in Dove Springs – a place where families in poverty come to get canned food, or clothes or school supplies for their kids.

Vargas says kids who parent kids often times drop out of school and that perpetuates the poverty cycle.

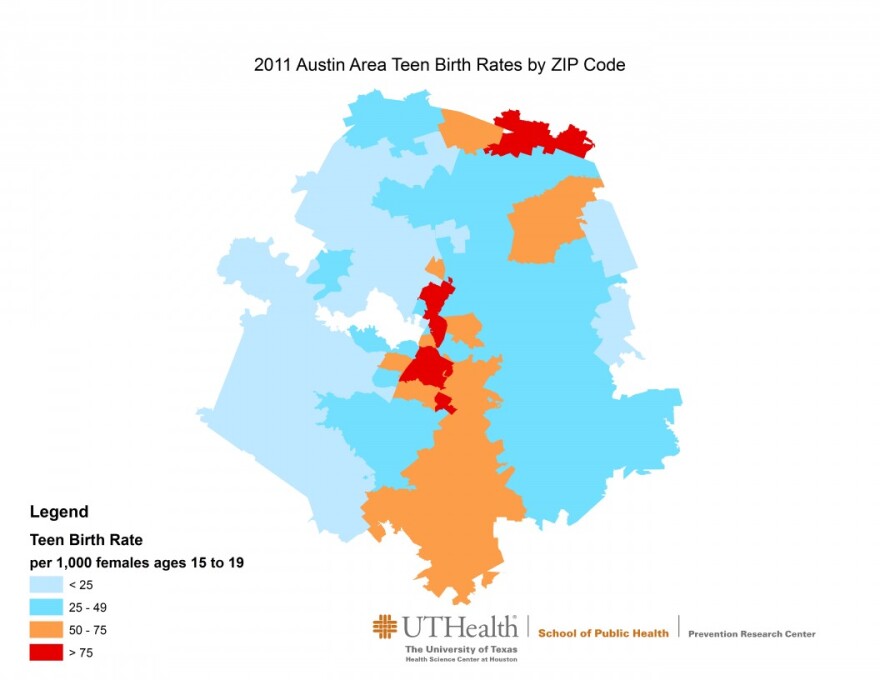

"It's not something I take pride [in]. Unfortunately, that is a reality in this community. We are number one in teen pregnancy in Travis County," Vargas says. "Here at Mendez we've had a few incidents. When I say a few, I mean one to two every year."

In 2010, the last year we have numbers for, there were 29 births in Travis County to girls 14 and under. From those 29 births, one baby was born to a white girl and one to an African American girl. The other 27 babies were born to Hispanic girls who were 14 or younger. The City of Austin is aware of the situation and believes something needs to be done.

Tim Eubanks is the man in charge of doing something.

Just a year ago, Eubanks was hired to lead a city program called the Austin Healthy Adolescent Initiative. He says his first focus when it comes to teen pregnancy is to shift the outreach a little and make sure boys are also targeted.

Eubanks is developing a curriculum that will be implemented starting this summer targeting areas with high numbers of teen births. He is partnering with local schools and a host of non-profits to do it. He’s aggressively breaking with the old programs – starting with the wording.

“Is the wording 'teen-pregnancy prevention?' or is the wording 'youth empowerment, positive youth development, youth leadership?' And, is it always about 'just say no' or is it also about – 'What does it mean to have a healthy relationship? What is consent? What is your own sense of your own self worth? So that you are not defining yourself in the context of just this other partner,'" Eubanks says.

In order to implement his program, Eubanks needs money. He says he’s applied for a number of grants and will know in the next few months whether he’ll get that money.

That has been a problem in the past. Of all the Texas cities applying for teen-pregnancy prevention funds last year, only San Antonio was approved.

Since this would be the first time Eubanks would be implementing his program, he’s hopeful about the future. But holds back when asked to predict the outcome.

One person willing to predict outcomes is Jordan Nicquette – the physician assistant. She says now that the Affordable Care Act is in place, she’s noticed small but meaningful changes in her patients’ behavior. In the past, a vast majority of them were uninsured, but she says that’s changed for some of them.

“Even with health insurance it would cost a woman – 30 or 40 dollars a month – just to pick up pills at a pharmacy and that can be a huge burden when you’re trying to decide between that and paying the rent," Nicquette says. "When you are 14 – you don’t even have that money. So, now, being able to give it out to people – discuss how to use it – that’s been a huge blessing just to have people try it out,”

For her part, Damaris Covarrubias hopes to have a positive impact on her younger siblings and on her younger cousins. As she fixes little Dalilah’s meals before heading to work, she says lately she’s done something nobody did for her: she’s spelled out the raw truth about premature motherhood with the younger girls in her family.

“I tell them don’t rush because then you will regret it. I was like, 'Live your life day by day, slowly, because once you are there that’s when you suffer the consequences.”

One of Damaris’ joys is school and she has vowed to not to quit until she gets her nursing degree.