Austin has its own convoluted history when it comes to school integration – one involving multiple federal lawsuits and many different strategies to desegregate schools.

Busing was one of those strategies. Many students were bused across the city to schools on the other side of town. West Austin residents went to East Austin schools and visa versa.

Saturday, May 17, marks 60 years since the Supreme Court struck down the concept of "separate but equal" in Brown v. Board of Education. It's a decision that affected students across the country. But for two Austin teenagers in the late 1980s, it also sparked a life-long friendship.

If you think about it, it’s a miracle Richard Reddick and Ryan Scarborough ever met. Scarborough, a white student from Austin’s Northwest Hills neighborhood, was bused to Johnston High School on Austin's east side, starting in 1986.

"There were really no options," Scarborough, now a lawyer in Washington D.C., recalls. "If you were in a particular part of the neighborhood or area, you were bused to Johnston."

In 1987, Austin ended crosstown busing; earlier that decade, a federal court ruled it had successful desegregated public schools. Scarborough could’ve gone back to his neighborhood high school, but he decided not to.

If he had, he probably would’ve never met Richard Reddick, an African-American from the opposite side of town. He came to Johnston his junior year, when Austin redrew its school boundary lines.

"Everyone would say to me, 'Oh, do you know Scarborough? You need to meet that guy, he’s on top of his game.'" Reddick says. "And so we met at some point and we hit it off instantly.”

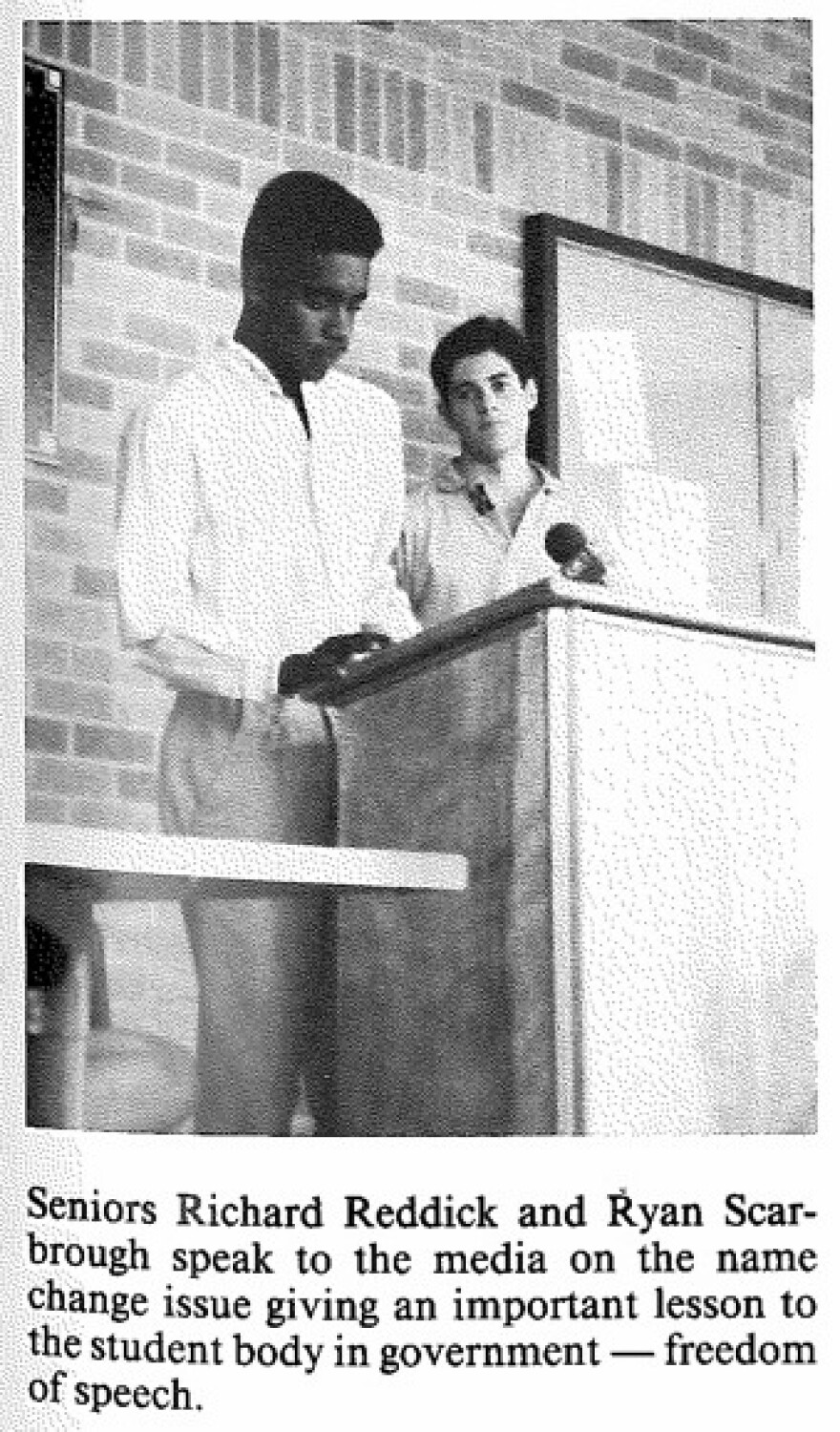

The pair even made Austin headlines their senior year when they organized a press conference in response to district plans to change their school's name.

"Us nerds, we don't have 'cool' alcohol or tobacco or marijuana stories – we hold press conferences illegally," Reddick, now a professor at UT-Austin's College of Education, jokes. "That's what we did for fun when we were in school."

Johnston High School was named for a Confederate war general (Albert Sidney Johnston). The pair didn't have "any love" for Johnson, Scarborough says, "but there was such an identity with the school and that name."

While many people’s most vivid high school memories are football games or prom, Scarborough and Reddick say what stood out for them was the diversity. Located in a predominantly black neighborhood, Johnston High School's population in the late 1980s was much more racially and economically mixed – mostly because busing brought students from all over the city.

“Being a lawyer now and knowing what Brown vs. Board of Education stands for, that really was the perfect manifestation of that Supreme Court decision," Scarborough says. “I was friends with people I never would've met because they didn't live in my neighborhood, did not have the same amount of money that my parents had, people who would not have had the same opportunities. And we were all together being taught by the same teachers and playing on the same sports teams."

During the 1988-1989 school year, the student population was 55 percent Hispanic, 19 percent white and 25 percent African-American. That was the first year students were allowed to return to their neighborhood schools, and while Scarborough says he remembers the amount of diversity dropping significantly in one year, there was still enough diversity to have a critical mass of most student groups. The Texas Education Agency does not have campus data readily available before 1988. But looking through his old yearbook, Reddick remembers just how diverse Johnston was during those years.

"You just see naturally diverse groupings of students and it was just the way it was," he says. "Nobody was making a point. We were just that way."

Teachers and administrators also took pride in that diversity. Teachers organized a march with Caesar Chavez and constantly reminded students about the school and the neighborhood’s history.

“I don't want to make it sound like it was heaven on earth and it wasn't a perfect school in a lot of ways," Reddick says. "[But] I saw low income kids who were high achievers and low achievers. I saw kids who were Latino and black who were high and low achieving.”

Today, Johnston High School is renamed Eastside Memorial High, and is mostly low-income, minority students. Two percent of students are white.

Scarborough says when he looks at the lack of diversity in his children’s school in Fairfax County, Virginia, he recognizes how special his experience was in high school.

"As I look back on it now and I look at kinds of schools my kids go to, I don't see the same level of socioeconomic mixing that I experienced when I went to high school," Scarborough says.

Reddick says it wasn’t until he became a researcher that he fully realized just how rare Johnston High School was when he attended. He’s sending his children to the new public Montessori school in Austin next year, with the hope that they will have a similar experience.