Following several years of rising housing costs, Austin’s political leaders are once again looking to the land development code to help with affordability.

The city’s land code limits what can be built on a piece of land. Hundreds of pages of rules dictate what you see when you look at a structure: how far back from the property line a house has to sit, how tall a house can be, how big a house can be.

Over the summer, Council Member Leslie Pool and her office decided, as others have before them, that they wanted to tweak these rules. They introduced a resolution that, if passed, will let people build up to three homes where just one or two are currently allowed. It would also lower the amount of land needed to build a house, although the vote on this part of the resolution isn’t until next year. Her office coined these changes HOME, or Home Options for Middle-Income Empowerment.

Pool and supporters of HOME contend this can help lower the cost of housing by allowing and encouraging developers to build more and smaller homes closer together, interrupting the landscape of large apartment buildings and single-family homes that define the city.

“It is designed to provide more options for homeowners and more opportunities for middle-income homebuyers in Austin,” Pool said at a press conference Tuesday. She was joined by other council members and union representatives for various low- and moderate-wage workers, including emergency responders. Those who oppose HOME warn it won’t do what supporters say and could instead worsen housing affordability.

The City Council is set to vote on these changes Thursday.

Wait. So, what would this do?

Currently, the vast majority of land in Austin is zoned so that a property owner can build one, maybe two, houses on their land. If council members pass the proposed changes, property owners would be allowed to build up to three homes on a lot. The city would also lower the amount of land needed to build a duplex and scrap rules limiting how many unrelated adults can live together.

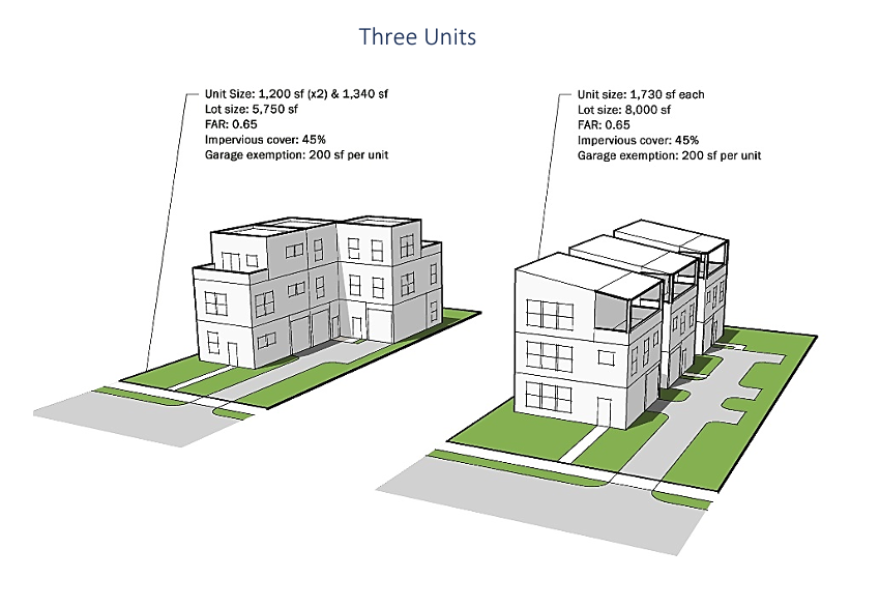

Council is set to vote on a second, and perhaps more monumental, round of land use changes next year. If passed, that measure would lower the amount of land a property owner needs to build a home. The minimum amount of land needed to build a house in Austin right now is 5,750 square feet, although the average size is larger – roughly 7,500 square feet.

Council members have proposed lowering the minimum lot size to 2,500 square feet. That would mean someone owning an average-sized lot in Austin could split it into three and build up to three homes on each plot.

Why are council members doing this?

Since 2020, rent and home prices have risen significantly. The median price of a for-sale home in Austin is now $540,000, a nearly 23% increase over three years. Rents rose 25% in that time. While housing costs have fallen this year, they’re still much higher than before the pandemic.

Building more housing can lower the price of housing. By letting developers build more in Austin’s central neighborhoods, supporters reason, prices overall will stay steady or drop. In one study of 11 U.S. cities, including Austin, researchers found that when new apartment buildings went up in a neighborhood, rents nearby were 5 to 7% lower than they were projected to be.

Council members and supporters of HOME also hope this will lead to the building of smaller homes which could also bring down the price of housing. Since 1991, new single-family homes in Austin have gotten larger, averaging nearly 2,300 square feet, according to data analyzed by Austin architects. Compare that to decades prior, when new homes averaged about 1,500 square feet.

What is the opposition against HOME?

Residents against these land use changes worry about potential impacts to the look of neighborhoods. Others are worried this will do nothing to bring down the cost of housing and that builders will be incentivized to tear down existing old, cheap homes, and replace them with new, expensive homes, effectively forcing people to move out of neighborhoods.

At the press conference on Tuesday, a group of protesters stood outside a media room and chanted “postpone the vote.” Solveji Rosa Praxis, a former Austin planning commissioner, was one of them. She said the city should require people building new housing to set aside one of these homes for people earning less than the median family income.

“HOME has no requirements for affordability, “ Praxis told KUT. “We want to keep communities here and that is why we proposed alternatives that will require that any units created are actually affordable to middle-income people.”

Research is mixed on the impacts new housing has on lower-income people living nearby. In one study of San Francisco, the researcher found that new housing encouraged wealthier people to move into a neighborhood and lowered the rate of lower-income people leaving; in other words, new housing increased gentrification but lowered displacement.

City staff has said they worry these rule changes could encourage a builder to buy an old, cheap home and demolish it, replacing it with three more expensive homes and that lower-income renters could be displaced as a result. In an attempt to mitigate this, the council will consider letting developers build more if they agree to preserve at least half of an existing home built before 1960.

Richard Heyman, who teaches urban studies at the University of Texas at Austin, said lower-income neighborhoods should be able to opt out of HOME.

“There is no question that there is a housing affordability problem in Austin, but I think that this is the wrong solution,” he said.

As it turns out, some neighborhoods may not have to abide by the HOME revisions. Neighborhoods that have private zoning, also called deed restrictions or restrictive covenants, could evade these changes. Many of these area-specific rules limit the number of homes that can be built on a plot of land. Neighbors who want to enforce these rules would have to go through the courts.

Have other cities done something like this?

Several years ago, leaders in Portland, Oregon, made it possible to build up to six homes on land where formerly it was more common to have two houses. That resulted in 44 homes being demolished and replaced with 267 homes, the majority of them fourplexes, or four homes attached.

In a report published a year after the changes, researchers found that developers built 204 fourplexes, the vast majority of which had two bedrooms. In most cases, each home sold for less than the home that was there before it but often not by much. In one case, a single-family home that would have sold for $572,000 was demolished and replaced with four four-bedroom townhomes. The average price of each townhome was $518,000.

So, will this work?

It remains to be seen how these changes will translate from the page to neighborhoods throughout the city. But politicians and supporters of HOME seem to think they’ve done what they can to get property owners and developers to build more and different kinds of housing.

There has been debate on how to ensure that new homes are smaller. Members of the city’s Planning Commission have zeroed in on a zoning tool called floor-to-area ratio, or FAR, which limits how much residential space can be built in proportion to the total square footage of a plot of land. It is one way to limit the size of homes that get built.

Sources have told KUT they worry the current FAR limits need to be lowered so that what gets built is smaller. Builders that spoke to KUT warned that limiting FAR too much could result in fewer homes being built. Not the duplexes, triplexes or townhomes politicians and supporters have imagined.

“Will it be enough to really provide housing in every neighborhood? I don’t know. I don’t know the answer to that,” Scott Turner, who runs the homebuilding company Turner Residential, said. “My concern is if we’re overly concerned about, ‘Oh, these units need to be small,’ well there’s a point at which they’re too small and it’s not enough of an [economic] incentive [to build them]”.

Turner and others who support HOME have said it is not a cure-all to Austin’s rising cost of housing, but it’s a start.