The word “equity” has been thrown around a lot over the last month, since the Austin Independent School District announced its plan to close and consolidate 12 schools. On the first page of the district’s proposal released on Sept. 5, it says these changes are being made “with equity in mind.”

But the meaning of the word “equity” means different things, depending on who you talk to.

As the district moved forward with gathering community feedback and answering questions about the proposal, equity, and what it means, was at the center of the conversation.

Equity vs. Equality

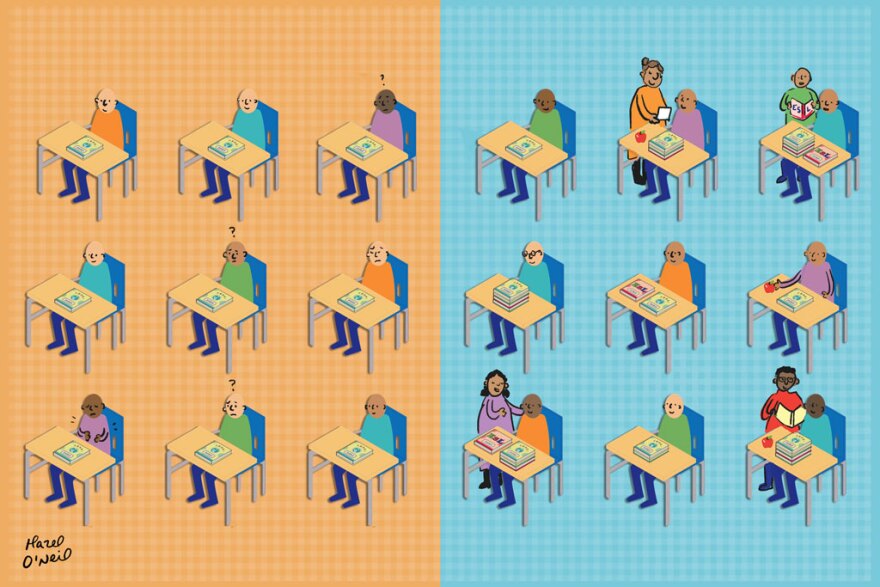

When talking about equity in education, you have to compare it to equality. Equality is when every student has access to the same resources: buildings, teachers, materials.

Equity is more nuanced. Some students need more resources because they have more needs, such as a child experiencing homelessness, food insecurity, trauma, diagnosed with a learning disability or any other challenge. They need more experienced teachers, support classes, one on one attention, smaller class sizes, or anything else that is often more expensive to implement in every classroom at every school in the district. Students without those challenges don’t need as many extra resources.

True equity means some children or some schools have more resources, but it’s aimed at getting those higher-need students to a similar outcome as every other student.

AISD and its board of trustees are using this definition of equity from the National Equity Project:

“Each student receives what they need to develop their full academic and social potential. Working toward equity involves ensuring equally high outcomes for all participants in our education system, to removing the predictability of success or failures that currently correlates with any social or cultural factor. Interrupting inequitable practices, examining biases and creating inclusive multicultural school environments for children and adults.”

But not everyone sees this definition reflected in the district’s proposal.

Equity Is...New Buildings?

When the list of closures was first released, many people criticized the fact that more schools east of I-35, which was historically the legally segregated part of the city and still where most low-income students and students of color go to school, are being proposed for closure.

At first, district officials defended this by saying there are more schools east of I-35, so proportionally there would be more closings there.

But after a few weeks, a new answer to this question emerged.

At one of the district’s community meetings, Austin ISD Superintendent Paul Cruz was asked why more schools in East Austin were chosen. He told the questioner that it was on purpose. He said the district chose more East Austin schools with low-income students because the district wanted to give them the opportunity to learn in a new school.

The district has said when it closes a school and consolidates it with another, it will build a brand new, modernized building to house all the students.

Equity Is...Not Impacting Low-Income Families?

New buildings don’t necessarily indicate equity says Rickey Lowe, a research associate for the Institute for Urban Policy and Research Analysis at the University of Texas. His group has studied school closings around the country.

“Having a new building for underprivileged kids sounds nice in theory but I think it’s more of a representation of equality as opposed to equity,” Lowe said. “Yes it’s going to be nice, it’s going to look modernized and it’s going to have all the trimmings that the school across town is going to have. But what about the actual programs, what about the teachers that are going to be there?”

There are also concerns about closing schools that, mostly, have a majority of low-income students, because this transition and displacement could have a bigger effect on those students.

That’s on the mind of Candace Hunter, a parent of a student at Maplewood Elementary, which is slated for closure. She’s also a former teacher who taught at mostly low-income schools in AISD. Hunter has seen the inequities that exist in AISD schools first-hand after teaching in schools with few resources, and sending her own children to a school with a lot of resources.

“I’ve been in a couple different schools and I've seen the inequity and I've seen the imbalance,” Hunter said. “Not just with program offerings but actual teacher quality. I visited my son at one particular middle school and I was floored at the lack of experience and support this teacher was receiving.”

She says those kinds of inequities add up and hurt a child’s education. Some scenarios in the proposal concern her from an equity standpoint. One example she points to is the proposed consolidation of Dobie and Webb Middle Schools.

Dobie is 94 percent low-income students, 59 percent of them are English Learners. Those numbers are slightly higher at Webb, where 96 percent of the student body come from low-income homes and 64 percent of them are English Learners. So these two student bodies have a lot of needs, and Hunter says the current proposal doesn’t address how to provide for them.

“You’re just doubling the problems,” she said.

She said if this consolidation came with a promise to provide instructional coaches for every subject at every grade level, as well as only hiring Master Teachers for the campus, she thinks it could work.

“That promise, I say go ahead and do it, it’s a fantastic idea,” she said. “Without that promise, we’re creating a situation we already have in the district.”

Research on school closings shows that if you consolidate schools, it’s best (in terms of academic outcomes) to bring students from different backgrounds together. So bringing together two groups of high-need students, like those at Dobie and Webb, could mean students will do poorly on state standardized tests.

On the other hand, the consolidations at Maplewood and Campbell, Reilly and Ridgetop and Pease and Zavala elementary schools follow what research suggests: combining high-income and high-performing schools with low-income and low-performing schools could yield the best results for students after a consolidation.

Equity Is...Affluent Families Shouldering The Burden?

There are many people pushing against any sort of closures. While most of the schools on the list of proposed closures have majorities of low-income students, three don’t: Maplewood, Ridgetop and Pease are comprised of mostly affluent families.

Maplewood parent Candace Hunter says if AISD has to go through with closures, these school communities need to remember: while it’s sad and uncomfortable to close their school, it’s actually equitable for them to be the ones that go through this transition.

“Especially for the Maplewood contingent, we’re giving up the least,” Hunter said. “We are moving. But for some schools, the consolidation will overburden the teachers, the parents. It will shock the students and that’s where our focus should be right now. Not that it’s an inconvenience that I have to drive another mile.”

Throughout the three weeks of community engagement meetings, parents, teachers and students shared their concerns about specific scenarios. In some cases, AISD officials said they hadn’t thought about those outcomes.

UT researcher Rickey Lowe says that’s how the district can improve this proposal to actually achieve equity.

“That is the only way to really address the equity, is you really talk to the community,” he said. “Not only just speak with them but you actually have to conduct research and compare it to other situations that may have or may have not worked and make sure the community is aware of what this process is looking like — as opposed to just doing a lot of guesswork and assuming these are the situations that need to happen.”

The Next Version Of The Proposal Will Be An Equity Progress Report

That’s what Stephanie Hawley, AISD’s Chief Equity Officer, says district administrators are doing now. They are looking at history and considering what they have heard from parents, especially communities that say their school building serves as a cornerstone of their community. Hawley says understanding history and research are important to achieve equity.

“We did not have those two pieces on the table. We do now,” she said. “We’re learning that we need to listen and prioritize what we’re being told by the people who are adversely affected.”

One thing she says AISD staff are considering is how the move to modernized building destroys the community at some schools. She says she values the feedback they have gotten from the community, because she says relationships with the community are how you build equity.

“We’re learning we need to listen and prioritize what we’re being told by the people who are adversely affected,” Hawley said.

Since the first version of the proposal came out, Hawley says, AISD administration and the school board have been undergoing equity training and are having tough conversations about all of this. She says if the training does what it’s supposed to do, the next version of the proposal will look dramatically different.

“That proposal will tell you where we are,” Hawley said.