Austin City Council members decided Thursday to postpone a vote on the bulk of new short-term rental rules that, if passed, would have made it difficult for owners to continue renting their homes without a city-issued license.

Mayor Kirk Watson told council members he wanted to wait out the current state legislative session before passing new rules, in the case that lawmakers pass a bill prohibiting cities from regulating short-term rentals. So far, no lawmaker has filed a bill that would outright do that.

“We are very dedicated to working toward a better system of short-term rental regulation in the city,” Watson said at a city council meeting Thursday. “We need to consider not only the current court rulings, but also conversations that are happening up the street at the legislature.”

Instead of overhauling rules as they have been discussing for months, council members instead moved ahead with one item: changing how the city collects taxes from short-term rental owners.

Property owners who rent out their homes on a short-term basis, which the city defines periods of less than 30 consecutive days, have to pay what’s called a Hotel Occupancy Tax. Historically, owners have paid these taxes directly to the city.

But now Austin will require short-term rental websites, such as Airbnb and Vrbo, to collect these taxes and send the money to the city. Airbnb has similar agreements with dozens of cities throughout the country, including Houston and San Antonio. Austin has told the companies to start collecting taxes on its behalf by April 1.

“We are supportive of platforms collecting and remitting local tourism taxes on behalf of hosts — something we have long advocated for here in Austin,” Luis Briones, senior policy advisor at Airbnb, said in a statement to KUT earlier this month.

This discussion isn’t new. Council members have been talking about requiring Airbnb and similar companies to collect taxes on the city’s behalf since at least 2017.

But at the time, some elected officials wanted the companies to share identifying information about those renting their homes in the hopes they could use this information to pinpoint short-term rental owners operating without a license. Short-term rental companies would not agree to this.

Ultimately, Austin’s move to have short-term rental sites collect taxes on its behalf could result in a jolt to its coffers. These companies would be collecting taxes from everyone who advertises on their site, not just those who, of their own accord, file these taxes with the city.

In recent years, Austin has collected about $7 million in taxes annually from short-term rental owners. This amounts to about 4% of the overall Hotel Occupancy Tax the city collects each year.

Per state law, these taxes can only be spent on items that promote tourism, such as arts funding, sports facilities or convention centers — something of particular interest to city leaders as Austin prepares to build a new convention center.

More changes could come later this year

Council members punted on other changes they planned to make to Austin’s short-term rental rules. That includes requiring sites like Airbnb to mandate owners provide a license number when advertising their homes.

Since 2012, Austin has required short-term rental owners to get a license. Currently, the city says it has nearly 2,200 active licenses.

But data from AirDNA, which collects listings from companies like Airbnb, suggests that thousands more people are using their homes as short-term rentals without a city-issued license; according to the company, close to 9,000 property owners advertised their homes as short-term rentals in January.

Austin’s intent to pass new short-term rental rules comes as cities across the country struggle to regulate these homes. In 2023, New York City attempted to enforce its strict limits on short-term rentals by requiring owners to register with the city. Dallas continues to fight a lawsuit over regulations it passed that same year.

In 2016, Austin adopted rules that would have, over time, outlawed short-term rentals where the owner does not live in the home.

But short-term rental owners sued the city. In two separate lawsuits, they argued that the city’s move was unconstitutional and violated their private property rights. Judges agreed, writing that Austin could not retroactively take away someone’s right to rent out their home on a short-term basis.

The city has interpreted these rulings to mean it cannot restrict the number of short-term rentals outright.

“What that tells us at this point is that we can’t have a blanket prohibition against existing [short-term rentals],” Trish Link, an attorney with the city’s law department, said earlier this month.

Instead, council members have proposed prohibiting an owner from running two or more short-term rentals within 1,000 feet of each other — a restriction, that because of Austin’s relative low-density, would theoretically only apply to duplexes.

Are short-term rentals killing affordability?

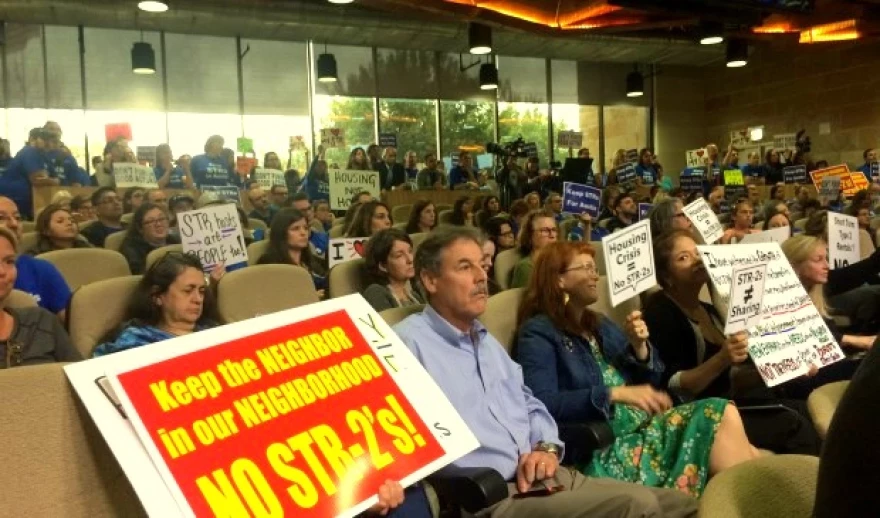

Residents have taken issue with this stance at recent public meetings. Some have described short-term rentals run as party homes and have urged the city to restrict the number allowed to operate.

Brian Klein and his husband live just east of downtown, in a ZIP code with hundreds of licensed short-term rentals. Klein told city commissioners earlier this month what it’s like to live close to a short-term rental run like a party house.

“[We can hear] people loudly stumbling from their Ubers back to their residences with sounds of vomiting and urination outside our bedroom,” he said. “Partying outside, screaming and blasting music between the hours of 10 p.m. and 4 a.m.”

Other residents have argued that short-term rentals make housing more unaffordable by taking homes that could be rented or bought by long-term residents off the market.

In other words, fewer homes leads to higher prices. Austin has proven this phenomenon recently, as rent prices have dropped in response to developers building thousands of new apartments.

“I’m really curious why we don’t … limit the amount of STRs available,” Hanna Lupico, who said she lives in a neighborhood where many homes are rented on Airbnb, told city commissioners. “Seems like a simple way to unlock housing volume.”

A study published in 2016 by a Harvard University law student looked at the impact of short-term rentals on housing prices in Los Angeles. The student found that rental prices in Venice, a neighborhood where about 13% of apartments were listed on Airbnb, were likely 2.5% higher because of the homes being rented to short-term renters in place of long-term residents.

The council is expected to wait out the current legislative session and return in the fall to potentially pass new licensing requirements.

Support for KUT's reporting on housing news comes from the Austin Community Foundation and Viking Fence. Sponsors do not influence KUT's editorial decisions.