On Dec. 7, 1941, 20-year-old Richard Yarling was in his fraternity house at Indiana University.

Thousands of miles away, something was happening that would change the course of his life: the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor in Hawaii.

The war had been going for a few years at that point, but the U.S. had tried to stay out of it. Until that day.

Yarling listened to the early reports coming over the radio, growing more and more horrified at what he was hearing.

“Of course we were all vitally concerned, being of draft age,” he said.

Yarling’s father had been a Navy man in World War I. The younger Yarling had joined the National Guard when he was 16. At 20 years old, he was prime age for the draft.

So, there really wasn’t a question about whether he would be going to war.

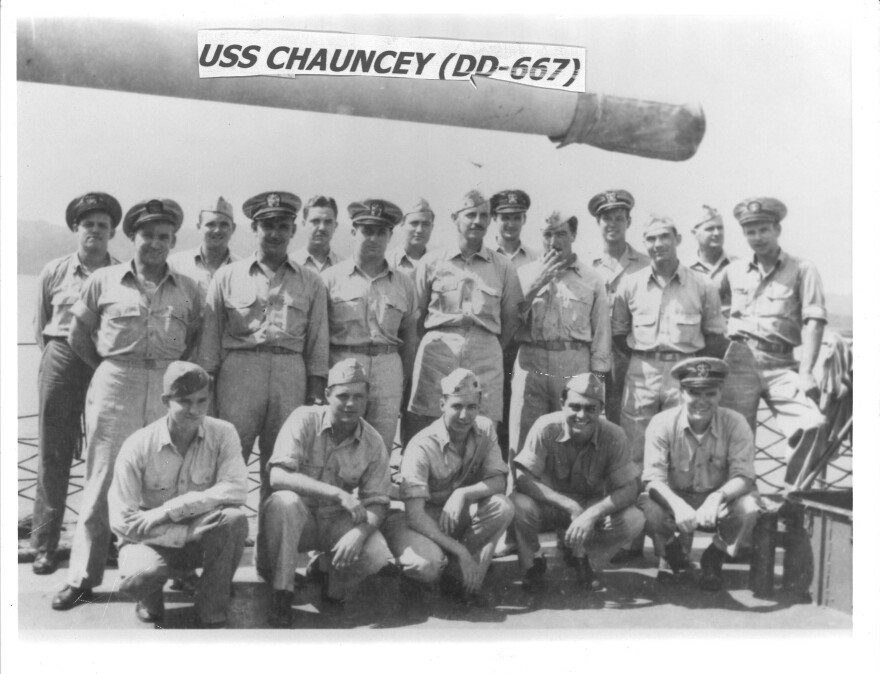

Yarling managed to defer the draft until he graduated college that spring. That's when he joined the Navy and before long, he was on a ship — the USS Chauncey — steaming out of New York and on his way to the war in the Pacific.

There were Japanese air raids. Storms threatening to swamp their ships.

“Those days [were] the most interesting — and also the most frightening time of my life,” Yarling recalled in an interview with the National Museum of the Pacific War in 2016.

In that interview, he talked about going ashore to an island and seeing bodies and body parts stacked 4 feet high like firewood. It was the carnage from a battle to take the island from the Japanese.

But he was proud of his service.

After the war, Yarling became a lawyer. He started a family and later in life he moved to Round Rock. He smoked cigars and drank red wine until he was 101.

Eight decades after the end of World War II, as Yarling was about to turn 103 years old, his granddaughter, Katheryn Stacer, had a question for ATXplained: “My question was if my grandfather, Richard Yarling, was the oldest living World War II veteran in the Austin area.”

Stacer submitted her question in September.

“A couple weeks [later], he actually passed away on the day after his 103rd birthday. It was not expected … but, I mean, he was 103,” she said.

Still, she wanted to know: Was her grandfather the oldest World War II veteran in the Austin area before he died?

Austin's many veterans

Austin has a history of long-lived veterans.

Richard Overton was, for a time, the country’s oldest World War II veteran. He spent his entire life in the Austin area.

Overton died in 2018 at 112 years old.

But since then, has there been a veteran in Austin older than 103, older than Yarling before he died in October?

Local veterans groups, including the Texas Veterans Commission and Honor Flight Austin, said they did not know.

But old TV news stories provide some hints.

Take Karl Schlessinger — who turned 106 last year.

Schlessinger was an airplane instrument specialist in World War II. He died this past January, less than two months shy of his 107th birthday.

So, no. Yarling was not the oldest living World War II veteran in Austin when he died last year. Schlessinger was about three and a half years older.

So, was Schlessinger the oldest? It’s hard to say. It’s a moving target.

But there is one person who might be the oldest living veteran in Austin right now.

His name is George Stowell Burson.

Burson was born in Fillmore, California. At a young age, he was interested in flying.

He and his friends would build box kites. To test them out, they would strap cats — live cats — wearing parachutes to the kites. They’d fly the kite up and tug on a string to open the cat’s parachute and the cat would float down to the ground.

The first couple times the cat did not like it, Burson said.

“But then all of a sudden it was waiting to go again! He enjoyed it eventually."

It made sense that when Burson was drafted, he joined the Army Air Forces.

'It was no picnic'

On Sept. 12, 1944, Burson was the co-pilot on a bombing mission. They were over Germany, headed to Czechoslovakia.

“We were flying along fat, dumb and happy and all of a sudden a fighter came and hit our tail,” Burson said.

Pieces were falling off their B-17 bomber as German fighters kept shooting. The pilot was hit. He was alive, but the engine was on fire.

“The pilot said ‘OK, everybody bail out!’”

Burson strapped on a parachute and made for the escape hatch. But there was a problem.

“There was a guy in there and he wouldn’t let go. I put both feet in his back and pushed with all my might and he went out,” Burson said.

There was a woosh as Burson was sucked out of the hatch, too. He was falling. He opened his parachute and landed in enemy territory.

Four of Burson’s crewmates made it out of the plane alive. Three of them died in the fighting. A fourth likely died when the plane crashed.

Soldiers captured the survivors and before long, Burson was at a prisoner-of-war camp called Stalag Luft I in the town of Barth, Germany.

If you ask Burson about his time in the Nazi POW camp, he downplays it.

“Oh, they treated us OK,” he said, casually.

Burson said mostly, it was boring. But it wasn’t as bad as some of the other POW camps. Prisoners at some other camps were forced to march hundreds of miles in winter when their camp was moved.

Meanwhile, Burson’s camp stayed put.

“So, it worked out real fine,” he said.

But Burson was a bit more upfront with his daughter, Mary Jane Burson.

“‘I would never go through it again. It was no picnic,’” he told her. “He said, ‘I have nothing to complain about compared to what other prisoners went through. Like the Japanese prisoners or even other prisoners of war in Germany or Poland or the concentration camps. So, I have nothing to complain about.’”

On May 1, 1945, Burson and the rest of his camp woke up to find the Nazi guards gone. A few days later the Germans officially surrendered to the Allies.

He was going home.

Years later, Burson took his family to Europe. They went to Germany. At some point, Mary Jane said she thought about how strange that must have been for him to go back to the country that held him prisoner. She asked him about it.

“He just said ‘You never blame the people for the actions of the government,’” Mary Jane said. “He said, ‘Those people I bombed in those factories? They had done nothing to me. They went to work to earn a living to feed their family, just like I had done.’”

Burson stayed in the military after World War II. He flew in the Korean War — and got shot down a few more times. After Burson left the military, he became a middle school math teacher in San Antonio.

He turned 104 years old this past May.

He was born five months before Yarling.

Does that make Burson the oldest veteran in Austin right now?

Maybe.

“I would have only wanted to know so I could tell him so he would have felt special,” Yarling’s daughter, Linda Hammel, said. “Because I already know he was special.”

Yarling and Burson had vastly different experiences of war, but those experiences shaped them.

“He never took for granted the fact that he survived that war and he lived every day to the fullest," Hammel said.

"It's very lonely"

Living that long can be isolating.

You may have family, but your friends — at least the ones who’ve known you longest — they’re gone. At some point you get to an age where no one around you remembers events that made you who you are.

“I can’t say he’s relishing it,” Mary Jane Burson said. “It’s very lonely. The other day, I said, ‘Well, whatcha doing today, Dad?’ He said, ‘Just sitting here waiting to die.' And I said ‘Well, you’re taking your sweet time!’ He said, ‘I know. It won’t get on!’”

He was joking, of course. But there’s an element of truth in every joke.

“I just sit in this chair and look out the window," Burson said. "There's nothing else to do.”

It’s worth thinking about how unlikely it is to live this long. Sixteen million Americans served during World War II. More than 400,000 of them died. Another 600,000 were wounded. On all sides, tens of millions were killed — but these guys survived and they watched it all happen.

Then they managed to make it another 80 years — itself a lifetime for almost everyone else. Car accidents. Illnesses. The shadow that stalks us all every day. They escaped it. They outran it.

They raised families, practiced law, taught math, drank wine and smoked cigars. They kept the memory of the deadliest war in human history and became a living reminder of what not to do to each other.

We’re approaching the day when everyone who served in World War II will be gone. Until then, it’s up to us to hear their stories, to learn from them and celebrate them — whether they’re the oldest one or not.

Support for ATXplained comes from H-E-B. Sponsors do not influence KUT's editorial decisions.