House Republicans have introduced legislation that some critics are describing as a national "Don't Say Gay" bill – inspired by the controversial Florida law that bans instruction on gender identity and sexual orientation in kindergarten through third grade classes.

If the federal bill were to become law, which is unlikely in the current Congress, its effects could be far more sweeping, affecting not just instruction in schools, but also events and literature at any federally-funded institution.

Here's what's in the bill – and what people are saying about it.

The bill's language is broad and consequential

The measure was introduced on Tuesday by Rep. Mike Johnson, R-La., and co-sponsored by 32 other Republicans.

"The Democrat Party and their cultural allies are on a misguided crusade to immerse young children in sexual imagery and radical gender ideology," Johnson said in a statement, calling the bill "commonsense."

The bill, called the "Stop the Sexualization of Children Act," aims "To prohibit the use of Federal funds to develop, implement, facilitate, or fund any sexually-oriented program, event, or literature for children under the age of 10, and for other purposes."

The language in the proposed legislation lumps together topics of sexual orientation and gender identity, with sexual content such as pornography and stripping.

It would prohibit federal funds from being used to support any "sexually-oriented" programs, events, and literature for children under 10; ban federal facilities from hosting or promoting such events or literature; and allow parents and guardians to sue government officials, agencies and private entities if a child under 10 is "exposed" to such materials.

The bill complains that some school districts have implemented sex ed programming for kids under 10, and that "[m]any newly implemented sexual education curriculums encourage discussion of sexuality, sexual orientation, transgenderism, and gender ideology as early as kindergarten." It also calls out events such as drag queen story hours in libraries, which it describes as "sexually-oriented."

The bill follows GOP-driven "parental rights" measures in Florida and elsewhere

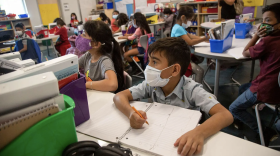

The proposed federal measure is framed in terms of parents' rights, a rallying cry on the right that in the last couple years has included battles against schools' COVID-19 vaccine requirements and fervent activism against critical race theory in classrooms.

In March, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis signed into law the "Parental Rights in Education" bill, which bans public school personnel from conducting classroom instruction on sexual orientation or gender identity in "kindergarten through grade 3 or in a manner that is not age-appropriate or developmentally appropriate for students in accordance with state standards."

Critics of the measure dubbed the Florida law "Don't Say Gay" and argue that its intent is to marginalize LGBTQ people and their families. A cascade of other states quickly introduced similar legislation, and Alabama passed its own version of the bill into law.

Among the proposed legislation's definition of the "sexually-oriented material" that it would limit, it includes description and depiction of sexual acts and "lewd or lascivious depiction or description" of human genitals.

But it also prohibits a full range of topics related to the LGBTQ community – "gender identity, gender dysphoria, transgenderism, sexual orientation" — that are largely about identity.

The bill's prospects are nil while Democrats control the White House and Senate

The bill would not pass in the current Congress, given that such legislation is solely a Republican effort and Democrats have a functional majority in each chamber.

Depending on the November election results, the makeup of the House and Senate could shift. Still, it's not clear how many Republicans would support the bill, even if it is popular among a certain strain of the party.

Even if the proposed legislation were to pass in a Republican-controlled House and Senate, it would be vetoed by President Biden. So don't expect this bill to go anywhere, for at least a while.

LGBTQ groups condemn the bill and warn against its potential effects

The Human Rights Campaign, which advocates for the rights of LGBTQ people, decried the proposed legislation.

"Extremist House Republicans like Mike Johnson are continuing their assault on LGBTQ+ Americans' ability to live their lives openly and honestly. A federal 'Don't Say Gay or Trans' bill ... is their latest cruel attempt to stigmatize and marginalize the community, not in an attempt to solve actual problems but only to rile up their extremist base," Human Rights Campaign Government Affairs Director David Stacy said in a statement.

Activist Erin Reed, who tracks anti-transgender legislation, argues that the comparison to a "Don't Say Gay" bill minimizes the potential effects of this proposed legislation.

"Don't Say Gay/Trans was focused on 'classroom instruction' which was bad enough," she wrote on Twitter. "This goes WAY beyond the classroom, and WAY beyond 'instruction.' "

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDA3MzEzNjc2MDEzMDI2Mzc4OTc4NTFmNg001))