This explainer was originally published April 10. It has been updated ahead of City Council's vote.

How do you retrofit a city that never planned for a population of nearly 1 million or for an extensive public transit system? Should you?

These are the questions facing council members as they prepare to vote Thursday on a slew of land use changes. Land use rules determine what can be built in the city and where. Elected officials and their supporters have increasingly turned to loosening these rules as a way to encourage builders to construct more homes in Austin and to help slow the increasing cost of housing and sprawl that has come to define this city.

Council members have been amending zoning rules bit by bit since 2020, when it became clear their plan to revise the city’s thicket of land development rules would be derailed by a lawsuit. But changing zoning rules in Austin is always controversial. People generally fall on one of two sides: Supporters say changes will allow more people to afford to live in central neighborhoods and make public transit more efficient; opponents worry enacting these changes will drastically alter the look of these blocks and the demographic makeup of the people living there.

Members of the council held a public hearing in April on a list of land use changes. The changes are scheduled for a final vote Thursday. Here’s what is proposed.

HOME Phase 2 or Minimum Lot Size

To build a house in Austin you need a certain amount of land, a rule referred to as minimum lot size. In 1931, the city adopted its first minimum lot size of 3,000 square feet. Over the next decade the city increased this number, eventually settling on 5,750 square feet in 1946. Austin’s minimum lot size has not changed since then and has ensured the city grew to look more like a suburb than a metropolis.

Elected officials now want to greatly reduce the minimum lot size. City staff have proposed more than halving it, whittling it from 5,750 square feet down to 2,000 square feet. (Single-family plots in Austin tend to exceed the minimum land requirement. The median size of a lot is closer to 8,500 square feet.)

It's possible that council members could go even further. Late last month, members of the city's planning commission recommended the council lower the minimum lot size to 1,500 square feet, roughly one-fourth of the current requirement. (Mayor Kirk Watson said Tuesday he'll propose 1,800 square feet.)

Council members are considering this change as the second part of a number of amendments they’re calling HOME. This formerly stood for Home Options for Middle-Income Empowerment, but is now being marketed as Home Options for Mobility and Equity. In December, council members passed the first round of changes, voting to let property owners build up to three homes on land where regulations historically allowed only one or two.

If the city’s minimum lot size is changed, property owners would be allowed to build one home on 2,000 square feet — or whichever number the council settles on. In order to build two or three homes, a property owner would still need at least 5,750 square feet.

Supporters on the council, including Mayor Pro Tem Leslie Pool, argue this will encourage property owners to carve up their land into multiple lots, as long as the lots are at least the new minimum lot size. Pool and others hope that faced with smaller lots and restrictions on size, developers would build smaller homes, which they hope will sell for less than large new homes and allow more people to live closer to the center of the city.

But opponents worry about the impact this could have on property tax bills and low-income renters. If developers can build more on a piece of land, they typically can reap more profit, making that land more valuable. This could encourage property owners to sell; if they were renting out a home, this could force tenants to move. It could also result in higher home appraisals and potentially higher property tax bills, although state and local policies adopted over the past few years have generally limited the rise of taxes, and in many cases even edged them down.

Compatibility

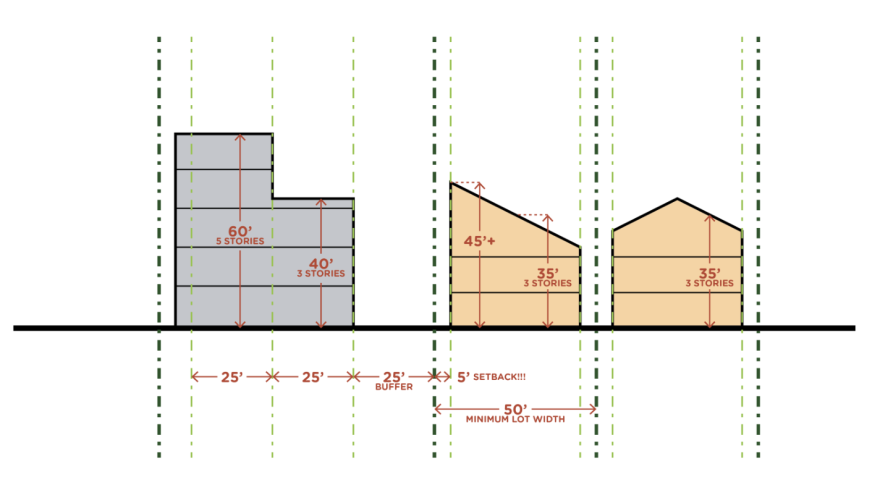

In Austin, there are rules that limit how tall a building can be when it is a certain distance from a single-family home or land that is zoned for a single-family home. The farther away from this property you get, the taller someone can build.

These height limitations extend up to 540 feet away, or the length of one and a half football fields, from a single-family home. Because the height increases with distance, the result is that the tops of buildings nearby often look like a set of stairs. You can see this in the design of the Alamo Drafthouse Cinema on South Lamar Boulevard.

The city has had these rules for decades and they are some of the most restrictive in the country. Elected officials are now proposing significantly loosening them. Instead of imposing height limits for structures as far as 540 feet away from a single-family lots, the council is proposing to cap height restrictions at a distance of 75 feet. Any building closer would have to adhere to some height limitations. (Council members passed an earlier version of these changes, but a judge struck it down.)

City staff estimate changing compatibility rules could allow developers to build nearly 63,000 new homes in Austin. At the same time, staff have noted that letting developers build taller in this way could encourage property owners to demolish existing apartment complexes, forcing renters to find another place to live. Staff estimates 252 current apartment complexes in some of the city's lowest-income districts could be redeveloped as part of these changes. They have not proposed protections for renters who could potentially be impacted.

ETOD, or Equitable Transit-Oriented Development

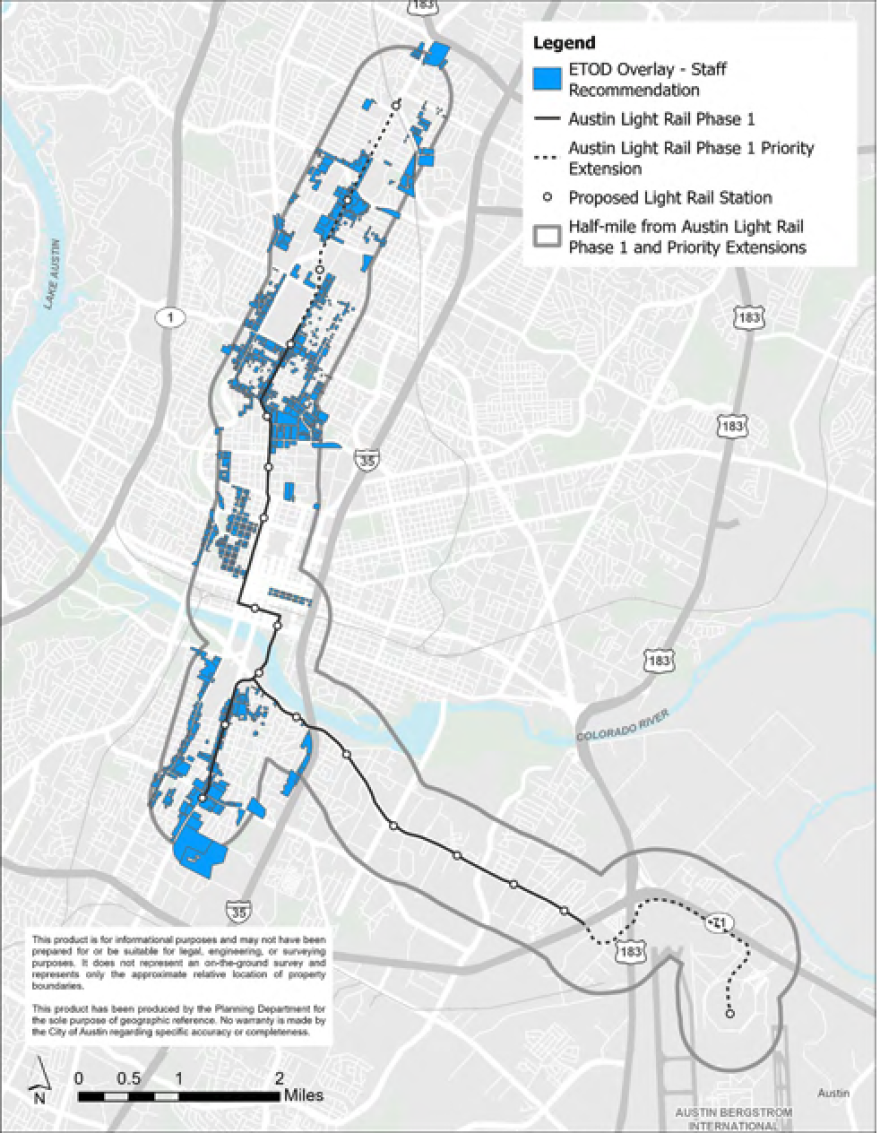

In 2020, Austin voters agreed to let the city raise their property taxes to help pay for a light-rail system, part of a larger project called Project Connect. In the latest iteration of plans, light-rail stations have been mapped for the UT Austin campus, downtown and parts of Southeast Austin along a route to the airport.

Elected officials are proposing to change land use rules within half a mile of stations with the intent of allowing more people to live near these future train lines. Developers would be permitted to build taller than currently allowed if they agree to set aside a portion, typically 12% to 15%, of what they build for people earning low incomes. In cases where they're building homes to sell rather than rent, developers could pay a fee instead of building housing for low-income residents.

As with compatibility, city staff have said these changes could encourage owners to demolish existing apartments to build taller buildings and potentially displace renters. But city staff is recommending protections against this happening. They’re asking council members to adopt rules that make it harder to redevelop buildings where tenants are paying cheap rents, and in the case that they do redevelop, tenants would get the option to rent a home in the new building.