The Austin City Council has adopted a long-term transportation plan – its first since 1995. It's a 337-page document, so there's a lot to unpack.

The Austin Strategic Mobility Plan is meant to cement how Austin's streets are designed and how both cars and buses and pedestrians (and scooters and maybe automated cars) occupy them.

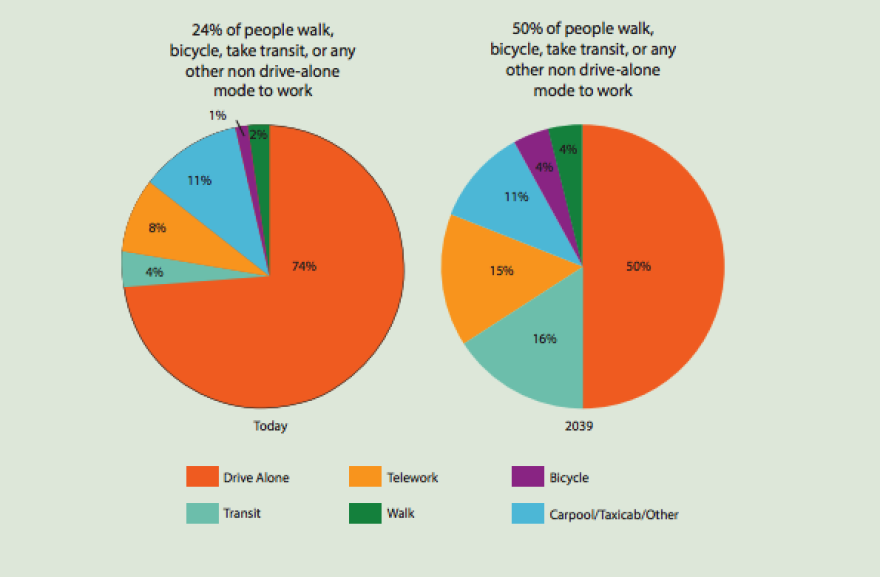

Ultimately, it aims to get fewer people to drive cars alone. The city wants a 1:1 ratio by 2039 – half the people in Austin taking a car alone, say, to work; the other half taking either a carpool, public transit, a bike, scooter or any other option. It currently estimates the ratio is 3:1.

To get where we are today, the city reviewed 52 plans or studies on transportation from 1998 to 2015. Sixty thousand people gave public input. The plan itself has been before six separate commissions in 2019 alone. That's because the Austin Strategic Mobility Plan combines all the city's previously written transportation-related plans – ones that it's already invested thousands, if not millions, of hours of labor, consternation and analysis – into a single plan. That includes:

- Bicycle Plan – The 2014 plan to expand the (then) 370-mile on- and off-street bicycle network, focused on increasing ridership, safety and connectivity by adding bike lanes.

- Sidewalk Master Plan/ADA Transition Plan – The 2016 plan to expand on the (then) 2,400-mile network of sidewalks in Austin and complete the 2,580 miles of missing sidewalks, which was estimated to cost $1.64 billion. A principal goal was to increase access and mobility for Austinites with disabilities, increase pedestrian safety and make neighborhoods more walkable.

- Urban Trails Master Plan – The 2014 plan to boost off-street, recreational trails and incorporate them more into the on-street bike routes, in addition to increasing money put into trail amenities – think lighting, wider trails and better maintenance.

- Vision Zero Action Plan – The 2016 plan to reduce traffic deaths to zero by 2025 by rethinking design principles of streets, high-capacity roads and corridors. The plan also focuses on increasing enforcement of traffic offenses in problematic areas and educating the public on safe driving habits.

- Pedestrian Safety Action Plan – The 2018 plan that suggests tweaking guidelines for stoplights at intersections across the city to be more pedestrian-friendly, installing improvements like pedestrian-hybrid beacons on busy roads to reduce distance to crossings, and slowing cars down by extending curbs or increasing lighting so pedestrians are more visible.

- Smart Mobility Roadmap – The 2017 plan emphasizes strategies to increase car-sharing and public transit use, and hypothesizes a future in which Austin adopts more electric and autonomous transportation.

To simplify: The ASMP lays out how the city will design roads, sidewalks, trails and bike lanes – and where it will prioritize projects. It also considers how those projects impact environmental and public health impacts. And, above all, it emphasizes multimodal transportation – that's a stilted term for cars-plus-everything else, because ultimately the goal is to get half of Austinites not to drive alone.

But there are uncertainties to reaching those goals that are out of the city's control.

One of the principal concerns related to traffic safety is speed. While Austin can change design standards to reduce speeds and reclassify speed limits on certain roads, that's not possible on roads that the state owns. The state doesn't let cities change what's called prima facie speed limits – the speed that best fits a road for its design and usage. Austin state Rep. Celia Israel has been unsuccessfully trying to get a bill passed to change that for the last two legislative sessions.

There's also Cap Metro, obviously, because transit is a key part of this plan. In December, the agency adopted Project Connect – its own vision-quest in the form of a long-term study – after a similarly prolonged public brainstorm. The "spine" of that plan, as Cap Metro puts it, is the future Orange Line, which plies the same route as the 801 Rapid bus route. Austinites will vote in 2020 on how to pay for that project – which could include a rail line, a rapid bus line or an autonomous bus.

And, because Austin is Austin, people have feelings about a lot of the policy and developmental implications. People hate density. People love density. People hate using dedicated bike lanes, if it means reducing car capacity. People love dedicated bike lanes, if it means reducing car capacity. Nobody's going to agree on all of it, but, regardless of where they stand, the city needs a plan – and City Council thinks this is the best – or, at least, most workable – one going forward.