Austin has nearly 70 low-water crossings that can flood during heavy rains, covering familiar roads with fast-moving currents strong enough to kill.

The city is working to fix these crossings. But it's going slowly. At the current pace of about one upgrade every three years, it would take more than 200 years to eliminate them all.

The biggest obstacle is money. Fixing one low-water crossing can cost anywhere from a few hundred-thousand dollars to millions. In a cash-strapped city with many competing priorities, drainage isn't always at the top of the list.

Low-water crossings are one of the most dangerous places to be during a flash flood. Until the Fourth of July floods claimed a staggering number of lives — at least 132 with dozens more still missing — most flood deaths in Texas each year happened at low-water crossings, according to the Texas A&M Transportation Institute.

As little as 6 inches of gushing water can sweep away a small car. For a truck or SUV, just 2 feet of flowing water can be deadly — an amount that can look deceptively passable.

"It's definitely a little nerve-wracking," said Gabby Marshburn, who commutes to a veterinary clinic next to a low-water crossing. "You think, 'Could I make it?' But you don't want to get swept away."

The city tries to stop people from taking the risk. Low-water crossings along Spicewood Springs Road have automatic gates that close during a storm. A few crossings have lights that flash automatically. But most require a city employee to drive out and manually close the gate.

The status of Austin's 67 low-water crossings is posted at ATXfloods.com, with hundreds more low-water crossings shown across Central Texas. In 2018, Austin installed cameras at some crossings so people could see for themselves how high the waters are.

The city also maintains an internal list of the 20 crossings most in need of repairs, based on how often they flood and how fast the water moves over them. And it has a map of the crossings that most frequently flood.

The crossing next in line for repair is on McNeil Drive, where a tributary of Walnut Creek regularly overwhelms the two 36-inch drainage pipes beneath the road. Even minor storms can force closures, cutting off a Northwest Austin neighborhood that has only one other way in.

"When it comes, it comes fast," said Brent Johnson, who lives next to the crossing.

"We've been up to our knees or our thighs on this road," his wife, Katie Johnson, said of the floodwaters. "It's just pouring."

When it pours, the rain brings more than water. The runoff spreads trash across the Johnsons' land, swamps their fences and has killed dozens of poultry they were raising.

"We got a trash can from Round Rock," Brent said. "We're not in Round Rock. It came all the way down to us!"

The city has been working for years to upgrade the crossing. The current design would replace the two metal drainage pipes with three 10-by-6-foot box culverts, larger structures capable of moving more water under the road.

The $2.1 million project is finally getting close to being built. It's now in the "permitting phase," meaning various city departments are making sure the design follows local rules, one of the last stages before construction.

But the Johnsons aren't happy with the plan. It's changed significantly from older versions and would cut into their land.

"The design sucks," Brent said. "Destroys the resale value of my house. That meadow that's there, they're going to take up a full third of it."

That kind of frustration is common. Every low-water crossing project requires balancing cost with safety benefits, engineering constraints and neighborhood concerns. Most people don't like having their property taken by the government, even if they are offered some compensation.

"Each project has its own unique situation," said Henry Price, a supervising engineer with Austin's Watershed Protection Department, a 400-person agency responsible for drainage in a city located in "flash flood alley."

Price said the city has already fixed many of the simpler projects that didn't require complex construction or controversial designs. What's left are the toughest cases.

"We got that low-hanging fruit," he said. "We're left now with some legacy ones ... just harder solutions. That really has slowed the pace."

So how does Austin compare to other Texas cities?

"At least they're making progress, which is what you want to see," said Chris Steubing, an engineer who has worked on floodplain issues for decades and now leads the Texas Floodplain Management Association. "There's probably some cities that aren't able to fund anything like that."

One major funding source is a drainage fee on city utility bills. It currently costs the typical resident $13.38 a month. Under the proposed city budget, that would increase to $14.05 next year.

Businesses have to pay the drainage fee, too, which is based on how much rain a property can soak up. More pavement or rooftop — impenetrable surfaces known as "impervious cover" — can mean a higher fee.

So the residential drainage fee is expected to generate $37 million this year. The commercial fee will bring in nearly $76 million. That money accounts for about 95% of the Watershed Department's revenue.

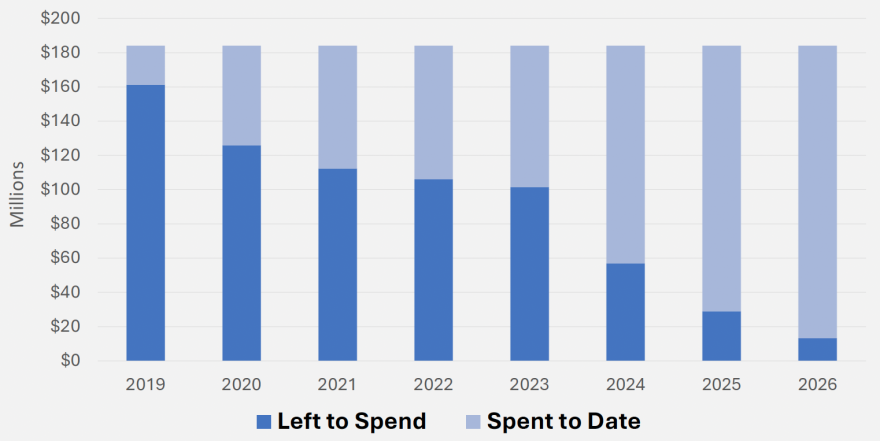

Another big funding source is bond money. In 2018, Austin voters approved $112 million for drainage and stormwater projects, paid for with higher property taxes. The bond included another $72 million to buy land for water quality protection: tracts where storm water flows into aquifers and the Colorado River.

Watershed officials said only about $30 million is left, and they expect that to be fully spent by the end of 2026, right around the time another bond election is planned.

As Austin expands, more pavement and rooftops increase runoff. And the city is more likely to experience intense rainfall, according to a comprehensive study by the federal government that prompted a redrawing of flood maps.

New development must meet stricter flood standards, so the number of low-water crossings isn't really growing. But the ones left behind from decades past are getting more dangerous and no easier to fix.