People of color in Austin can expect their homes to be worth nearly three times less than homes owned by white residents, according to a new report.

Researchers with Washington University in St. Louis and the University of Illinois-Chicago found that while the average appraised value of a home in a white neighborhood in Austin is $873,758, a similar home in a community of color is valued at $318,496.

“The amount is striking, but it's not surprising,” said City Council Member Vanessa Fuentes, who represents Southeast Austin. Fifty-five percent of Latino families living in Fuentes’ district own their homes, which is the highest rate of Latino homeownership among the city’s districts. “I think everyone here in Austin knows the extreme racial wealth divide that we have and the racial inequities that we have.”

Researchers looked at "comparable" neighborhoods, including parts of town with the same level of employment and amenities, such as parks and shops. By controlling for these variables, the report’s authors said, they were able to show that race plays an outstripped role in what homes are worth.

“Austin follows the pattern that we're seeing across the nation,” Junia Howell, a professor at the University of Illinois-Chicago who co-authored the study, told KUT. “That homes in white neighborhoods are valued considerably higher than homes in communities of color.”

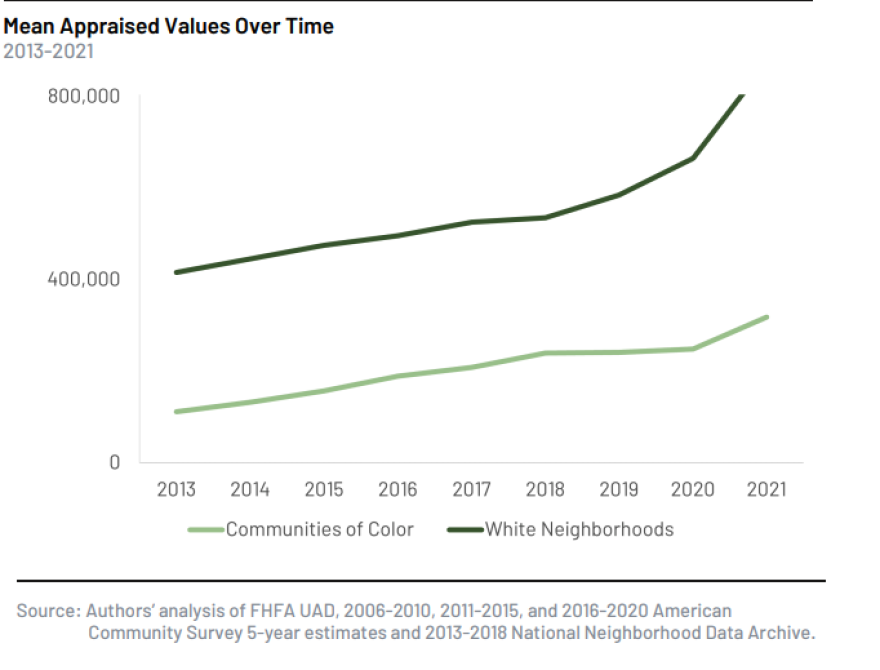

And that only worsened during the pandemic. In 2013, the difference in the average values of homes in white neighborhoods and communities of color in Austin was about $300,000. Last year, according to the study, it rose to more than $500,000.

This graph shows appraised values for homes in Austin over time:

“We had a completely unprecedented inequality growth in home values during the pandemic,” Howell said.

Researchers have long struggled to understand how racial bias shows up in home appraisals without comprehensive data. They've often had to rely on poor data or anecdotal accounts.

“I had kind of given up hope that we were ever going to get the data,” Howell said.

But that changed last week when the federal government released millions of appraisal values to the public.

Before someone buys a home or refinances a mortgage, an appraiser estimates what the house would sell for. They typically do this by considering the recent sales price of similar homes nearby.

That can be thorny, though, when you consider the history of homeownership in America. Once long-term mortgages became widespread after the Great Depression, many families were able to afford to buy homes for the first time. But these mortgages were only available to white families, particularly white families looking to buy in white neighborhoods.

Paired with other racist policies, the values of homes in white neighborhoods became much higher than those in other parts of cities.

Steve Kahane, a Houston appraiser who serves as the president of the Association of Texas Appraisers, said he acknowledges that today’s appraisal values can still reflect the history of racist homeownership policies but that doesn’t mean appraisers themselves are actively discriminating against people.

“I'm not so naive to seem to believe or suggest that racism isn't real or doesn't occur,” he said. “But if market participants … if they're paying more to be in a certain neighborhood because it's the ethnic makeup that they like, then that's that. Our job is to reflect what market participants are doing.”

Howell and her co-author, Washington University professor Elizabeth Korver-Glenn, advocate for overhauling appraisal methods and valuing homes on what they cost to build, for example, instead of what someone is willing to pay for them.

“When we are using an appraisal method that is historically rooted in racism and contempt … we are furthering this inequality every time we're allowing home prices to quickly appreciate in some areas and lag so far behind in others,” she said.

Awais Azhar, who serves on the board of the nonprofit HousingWorks Austin, said it further harms people of color to sell them on the idea of homeownership if they don’t benefit from it in the way white people are poised to.

“We're trying to get people into homeownership, but when even those folks are able to access [it], we're not able to give them the same wealth-building options or, honestly, living options as white people,” Azhar said.