This story was originally told live at the Paramount Theatre on April 3, 2024.

If you’ve visited East Austin around Springdale and Airport Boulevard in the last several years, you’ve likely noticed apartment blocks, offices and cafes sit where truck depots, warehouses and vacant lots once sprawled.

At seven-years-old, Springdale General — a studio, retail and business campus — is the most established of the new arrivals. Across the street, a five-story apartment complex, The Goodwin, is still getting its finishing touches.

Next door, the wavy glass facade of the Springdale Green office building projects a smooth modernity. A sign in front advertises space for lease.

“You’d never think that it was just some big industrial lot for a long time,” said Andi Acevedo, a neighbor who has watched the buildings go up with interest and some concern.

Many of these blocks used to encompass something called “tank farms” — the focus of one of the greatest environmental controversies in Austin’s history. There were toxic spills, lawsuits, protests — all stuff Acevedo learned after she moved down the street several years ago.

This history has left her with a lot of questions. But the biggest one, which she put to KUT’s ATXplained project, is pretty simple: Is the land safe to be on?

It’s a question Austinites will likely be asking more often, as infill development takes place on city lots formerly occupied by polluting industries and businesses. Developers and public officials say existing rules ensure health and safety, but those rules allow some contamination to remain.

The battle over tank farms

Despite the name, tank farms are not farms at all. They are facilities where crude oil, gasoline and jet fuel are stored in big tanks before they go to gas stations, airports or wherever else petrochemicals are used.

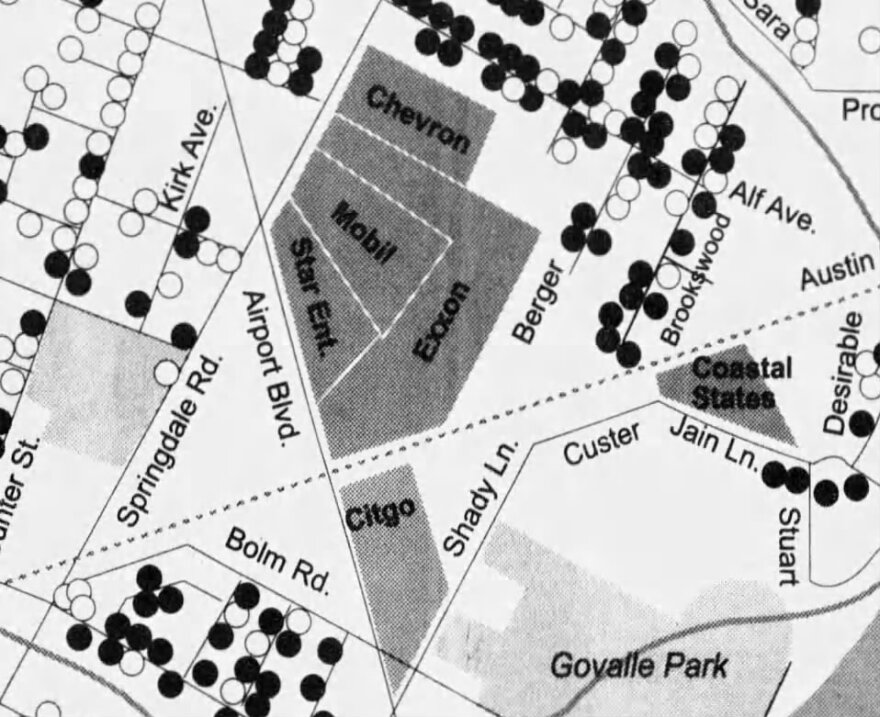

The first tank farm came into this part of East Austin in the 1950s. You can find old aerial photos showing how that tank farm was soon joined by others, more and more being built right in the same area.

This was by design.

The land was near the old Mueller Airport, which needed fuel. There was pipeline access, and, crucially, the city had made the zoning inviting for this kind of industry.

"The siting of hazardous facilities was open to whoever wanted to locate in that area,” said Sylvia Herrera, a longtime environmental activist who grew up near the tank farms. “So you have hazardous facilities next to schools. You have hazardous facilities next to residences.”

Those schools and residences were likely occupied by working-class, Black and brown communities, like the one Herrera grew up in.

This was also by design.

For decades, the same city zoning that had put heavy industry on the East Side also pushed those communities there.

"That was all impacting the communities’ health,” Herrera said.

The policies are now recognized as a textbook example of environmental racism. But, she said, a lot of people back then didn't understand the pollution they were being exposed to.

That started to change in December 1991.

At the time, Herrera was a single mother of two, living a couple blocks away from the tank farms when she noticed something in the newspaper.

“There was a public notice, in small print of course, saying that Mobil [Oil] wanted to build another tank,” she remembered.

Along with the notice was a list of the chemicals the tank would emit into the air: benzene, nitrogen oxide, carbon monoxide, gasoline and diesel fumes.

It occurred to Herrera that the notice was just for that one particular tank.

“You start counting all the tanks that were already there,” she said, “and you can imagine all the pollution that was coming out of there.”

Herrera was a member of a local environmental group called PODER. It decided to do a health survey of the neighborhood to see what kind of impact the tanks were having. Members went door to door asking residents if they were experiencing problems.

What they found was frightening.

People reported “migraine headaches, respiratory problems like asthma or coughing and having nosebleeds and so forth,” Herrera recalled. “It was three-fourths of the community that was having the same symptoms!”

Neighbors started organizing to kick out some of the biggest companies in the world — Chevron, Citgo, Mobil Oil, Exxon.

“We didn’t have any money,” Herrera said. “Here we were fighting these oil giants. But people had the will.”

They held protests outside the tank farms, put pressure on state politicians and raised their voices at City Council meetings.

The deeper Herrera and others dug, the worse the oil companies looked. Toxic waste had seeped from the tanks into the earth and the groundwater under the community. The public had been kept in the dark about dangerous air emissions.

The Travis County Attorney even opened criminal investigations.

For those living nearby, the tank farms had become an existential threat. For the oil companies, they had become the source of some very bad publicity.

One by one, the “oil giants” agreed to shut down their tanks and move.

That's how a group of East Austin activists took on some of the world’s largest oil companies and won. It's the kind of victory that rarely happens and has since become an important part of Austin’s history, celebrated by city government, studied by academics and memorialized in public art.

But for Herrara, the story is bittersweet.

For one thing, she said, much of the community that fought that battle has been displaced.

“All these areas have become gentrified,” she said. “And so it’s sad to see, because it’s not progress for our community.”

For another thing, some of the contamination stayed in the ground — even after the tank farms were dismantled.

That was allowed because of a deal the oil companies made with the state. Instead of fully cleaning up the land, the companies put deed restrictions on the properties that, regulators said, would protect the public from potential toxic exposure. The deed restrictions allowed only industrial or commercial use.

Simply put, no one could ever live there.

The church vs. the oil company

While they did not return the land to its original condition, the former tank farm owners did hope the earth might heal itself.

The process, sometimes called “self attenuation,” assumes that rainwater might naturally flush toxins out of the soil.

“They just left these properties and let the rainwater do what the rainwater was going to do and let the earth do what the earth does," David Gottfried, a lawyer who works on real estate cases, told KUT in an interview back in 2016. "And they would monitor it.”

He said for years the oil companies tested the groundwater and treated the water that came up dirty.

Many of the lots sat empty. Then one day in January 2000, a group came along that wanted to buy. They were a religious congregation called La Voz de la Piedra Angular, The Voice of the Cornerstone.

“They purchased the property to establish their church,” said Gottfried, who went on to represent them.

While many found the former tank farm land undesirable, he said, for this particular church, it was perfect. That may have been because the congregation had some unique beliefs about how much time there was left for them to build.

“They believed in the apocalypse,” he said. “They needed a very large piece of property, because they believed that the apocalypse [was] coming."

So they took one of the huge warehouses that stood on the land and converted it into a place of worship, installing a stage and altar. They put in a kitchen and offices to run businesses out of the property.

“Then behind the building,” Gottfried said, “they made a baptismal pool and they were performing baptisms.”

According to court documents, the church had converted an old fuel tank into the pool. Gottfried didn’t remember it that way. But, regardless, the baptisms caught the attention of the site's former owner: Exxon.

“Exxon was very unhappy about that,” he said.

Even though the company no longer owned this property, it still had the power to enforce the land-use restrictions it had put in place. It also had reason to — if someone got sick due to the pollution left on site, it could be sued.

The church had not been informed of any land-use rules when it moved in, Gottfried said. But that didn’t stop Exxon from suing. The oil company wanted the church gone.

“They were just minimizing their liability,” Gottfried said. “My position on that is that if Exxon really wanted to minimize their liability … they should have cleaned it up!”

Gottfried argued the church should be able, at least, to stay and pray. He pointed out that commercial activity was allowed under the deed, and that there was nothing specifically prohibiting religious services.

Gottfried remembered the judge agreeing that the church could hold a shareholder meeting there.

“I said, ‘And after that shareholder meeting can they all stand up and join hands and recite the Lord’s Prayer?’” he recalled. “She said ‘no,’ and we lost the case.”

The church is still around, just not in that location. I called the pastor to get a comment for the story, but he didn’t want to talk.

Why?

“Está en el pasado,” he said. It’s in the past.

But to this day, the case remains an example of how what’s allowed on polluted land can be as much a legal question as an environmental one.

Testing for toxins

After Acevedo learned about the toxic legacy of the tank farms, she tried to look into what clean-up work had been done ahead of all the new construction.

“There's not a lot of good information,” she said. “It left me with a lot of questions.”

Questions like: “How does a place where people aren’t allowed to live become suitable for so many other uses?”

KUT requested an interview with Austin’s Planning Department, which approves new development, and Austin’s Watershed Protection department, which handles many environmental matters.

Both said no.

The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, the state agency that oversees Texas environmental policy, answered some questions on background but also denied an interview request.

Fortunately, Michael Whellan, an attorney who worked for the developer of the Springdale Green office project was available.

“First and foremost, this is a city process,” he said. “The only control the state has was its involvement in cleaning up the site. That's through the TCEQ.”

After the church left in 2007, the TCEQ decided that the groundwater pollution at the site no longer posed a threat to neighboring lots. So, regulators told Exxon it could stop monitoring and treating the site.

“All water monitoring wells had to be capped and shut down,” Whellan said.

Exxon appears to have gotten the deed restrictions changed about seven years later to make it easier to build on the land, still barring any residential use.

By 2020, a real estate boom had hit Austin. Parts of East Austin, once on the city’s outskirts, were now considered central. The former tank farm land was hot property.

The developers that bought Springdale Green took soil samples as part of the building process.Those samples showed the soil quality had not changed much since Exxon left in 2007.

But, after looking at the test results, the TCEQ said the soil would be OK to use as “fill” beneath the new construction.

The city approved planning and building permits for the property. And work began on Springdale Green.

Whellan said that work required a lot more cleanup just to start construction. For example, a pipeline was found that one of the oil companies had neglected to declare with state regulators. It cost the developer over $250,000 to have it removed, he said.

For Whellan and many others, the lot’s redevelopment is an example to be followed, a success story of urban planning.

He said the developer created a stormwater drainage system to mitigate flood risk in the surrounding streets, removed invasive species and invested in an affordable housing fund. The Springdale Green project also got gold certification from SITES, a group that recognizes “sustainable and resilient landscapes and other outdoor spaces.”

All across Austin there are contaminated areas that used to house everything from old factories to gas stations that could be put to new use.

“We have to continue to identify where these sites are, make sure they get cleaned to at least commercial standards, and not remain vacant," Whellan said.

But others, like Acevedo, remain uneasy.

“On this side [of the street] there's a ban on building residential units,” she pointed out. “But then like directly across the street there's residential properties being built.”

“I hope that it doesn't cause any health problems for anyone.”

The fact is, in a system where polluting companies are allowed to leave without cleaning up completely, that anxiety will likely remain.

Yard garden?

There was another way to gauge the long-term impact of the tank farms in Acevedo’s neighborhood: test the soil for toxins.

KUT sent soil samples taken from her backyard to a private lab that specializes in testing for dangerous metals and petrochemicals. The results showed earth that was free of any major contamination.

While the tests provide only one small data point in one backyard, they appeared to assuage some of her concerns.

She said she may even start a vegetable garden.