Austin, deep in drought up until this month, is now watching its severely depleted water reservoirs rise to levels not seen in years. This week the Lower Colorado River Authority even had to open four floodgates on Lake Buchanan for the first time since 2019 to manage the flow.

The shift from disastrous dry spell to over-saturation is dramatic, but not unheard of.

“Historically, we go through lengthy drought periods that are then broken by significant major flood events,” said John Hofmann, executive vice president for water at the Lower Colorado River Authority. "While we don't often have them in July, it's not unprecedented.”

But those fast-filling reservoirs did more than replenish water supplies, they also stopped more devastating flooding.

“Imagine the Colorado River through Austin with nothing to prevent those floods from rushing through town or anywhere along the river," said Robert Mace, executive director of the Meadows Center for Water and the Environment.

We don't have to imagine.

Between Austin's founding in the 1830s and the beginning of the reservoirs' construction in the 1930s, the Colorado River flooded regularly.

It was really bad. Massively destructive flooding seemed to happen about every 10 years on average. Floods wiped out city dams, overtopped bridges and killed hundreds.

One event washed scores of dead buffalo from the high plains all the way to the streets of Austin. Another formed a lake 65 miles wide between the mouths of the Colorado and Brazos rivers.

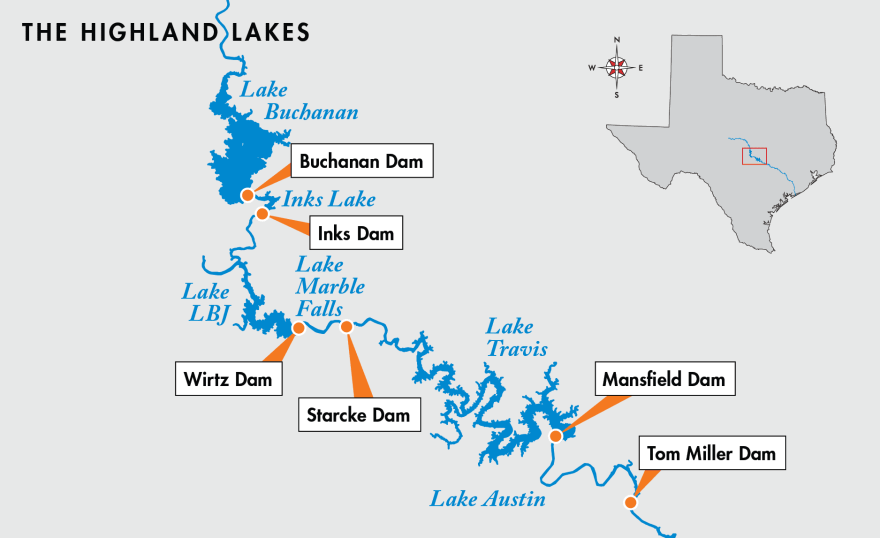

That pattern of floods stopped with the completion of the system of dams and reservoirs — often called the Highland Lakes — designed to hold in floodwaters and generate hydroelectricity.

Two of those lakes, Travis and Buchanan, also store the region’s water supply, and Lake Travis maintains extra space to store excess floodwaters.

When flooding rains come, the LCRA staffs a river operations center around the clock to monitor the water coming into the system and figure out when to store or release it downstream to decrease flood risk.

It was the anticipation of more water coming into the lakes from upstream that prompted the LCRA to open the floodgate this week, passing some water from Buchanan, which was filling to capacity, down to Travis, which still has storage space left.

“It's really critical in our part of the world that you have streamflow gauges to support your decision-making,” Hofmann said. “We have over 275 gauges in our hydromet system that allow us to basically have eyes on what's happening out in the watershed. So we're less likely to be surprised by these flash-flood events.”

Of course flooding still happens in Austin.

A brief history of flooding

Most of the recent deadly floods in the city — including the Memorial Day floods of 1981 and 2015 — were caused by flooding of local creeks, not rivers.

With no system to capture or control the flow of water in those creeks, rainwater can quickly overtop banks and crash into streets and neighborhoods, just like what happened last week in Travis County’s Sandy Creek area.

But river flooding has also been an issue.

In 2013, Lady Bird Lake flooded nearby parks and streets after mechanical problems with the floodgates on the Longhorn Dam, which the city — not the LCRA — operates.

In 1991, heavy rains caused river flooding downstream from Austin, prohibiting the LCRA from releasing water from Lake Travis and causing the reservoir to reach its highest level ever recorded — less than 4 feet below the Mansfield Dam spillway.

That flood swamped 300 homes that had been built in the floodplain of Lake Travis — though officials said the results could have been far more ruinous without the reservoir in place.

Experts also said massive rains will likely fall some day at exactly the wrong place and time. That could overwhelm the LCRA's system of water management and bring disastrous flooding back to the Lower Colorado River.

According to a city of Austin report, "an LCRA study estimated that a Hill Country storm like [2001's Tropical Storm] Allison would have forced LCRA to open all 24 of Mansfield Dam’s floodgates — something that has never happened. (The most that have been opened at one time was six, during a 1957 flood.)"

“One day such a flood will occur, and its impact will be even more devastating to a basin that is much more heavily populated and urbanized than it was seven decades ago,” LCRA's chief meteorologist, Bob Rose, is quoted as saying.

Plenty of room left in reservoirs

But, this time around, Colorado River flooding does not seem to be in the cards.

While Lake Buchanan has now filled to capacity, Hofmann said, Lake Travis — which is currently 87% full — will likely stay a few feet under full.

If Lake Travis' water storage space were to reach capacity, any additional floodwaters would enter its "flood pool" — extra storage space maintained to prevent water from cresting the lake.

Hofmann said that flood pool, currently empty, can store a lot of water.

“The flood storage is almost as much as the water supply storage at Lake Travis,” he said.

That means there is still effectively another Lake Travis’ worth of space upriver to gather in more floodwaters in the event of more rains.